© Laisa Watsko

“You were here, remember?”

THINK OF THE MOUNTAINS WHEN YOU TELL THIS STORY. A voice over the phone instructs me to remember my first time visiting the hamlet of Ausuittuq. I see immense mountain ranges all around, cloaked in a permanent blanket of snow and the Arctic Ocean at the hems of its shores. At the base of the mountains stands a statue of a woman holding a child.

Their gaze, directed towards the ocean, carries a sombre expression that evokes a period characterized by a profound displacement. The settlement of Ausuittuq was founded on the fragmentation of Inuit families starting during the 1950s. This story may begin here, but it highlights a decade of Inuit vitality achieved through community, the reclamation of language, and land. Nearly four decades later, we find Iga and her family’s life in “the place that never thaws.”

As an urban Inuk born and raised in the traditional territory of Anishnaabe First Nations, or the southern region of the province of Quebec, my ambition to celebrate and explore my culture and Indigeneity has led me around the world from Aotearoa to Nunavut. In 2019, I took the exceptional opportunity to travel and teach STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) education throughout the Qikiqtani region. During my first trip to Grise Fiord, Ihad the privilege of meeting Iga, a teacher at Umimmak school. Iga has graciously shared stories from her life, giving insight into her passion, and hopes as an Inuktitut cultural teacher. Through my account of phone conversations between Iga and myself, I hope to illustrate a moment in contemporary Inuit Nunangat within the context of (whatis currently known as) Canada.

Iga was born in the High Arctic community of Kangiqtugaapik, also known as Clyde River. Her father was an RCMP constable stationed in Ausuittuq, and at a very young age, she would be sent to join her family. In the early sixties, Iga recalls the traumatic experience having been a young child with tuberculosis. She has few memories of that time; most prominent are the several traumatic weeks alone on a ship and the fear that she may never return to her family. These memories from her childhood would resurface throughout her life, especially when she began working at the community health centre in the early nineties. As a working mother in the mid‐eighties and early nineties, Iga found strength through her family to work at the health centre.

© Laisa Watsko

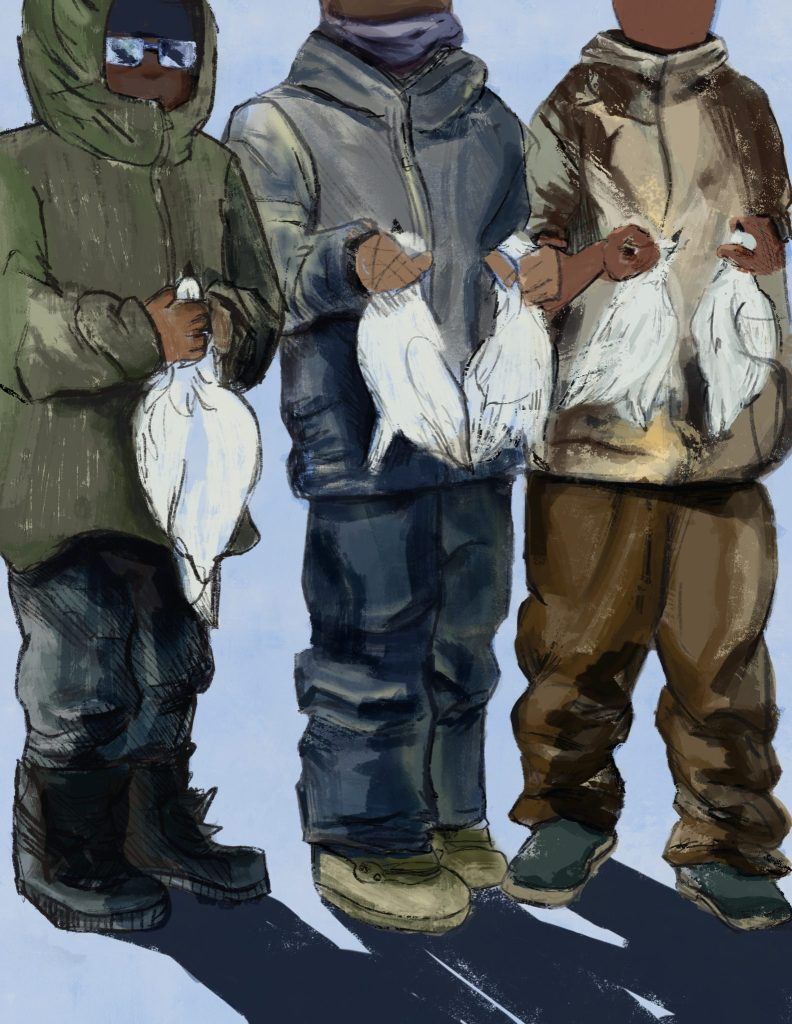

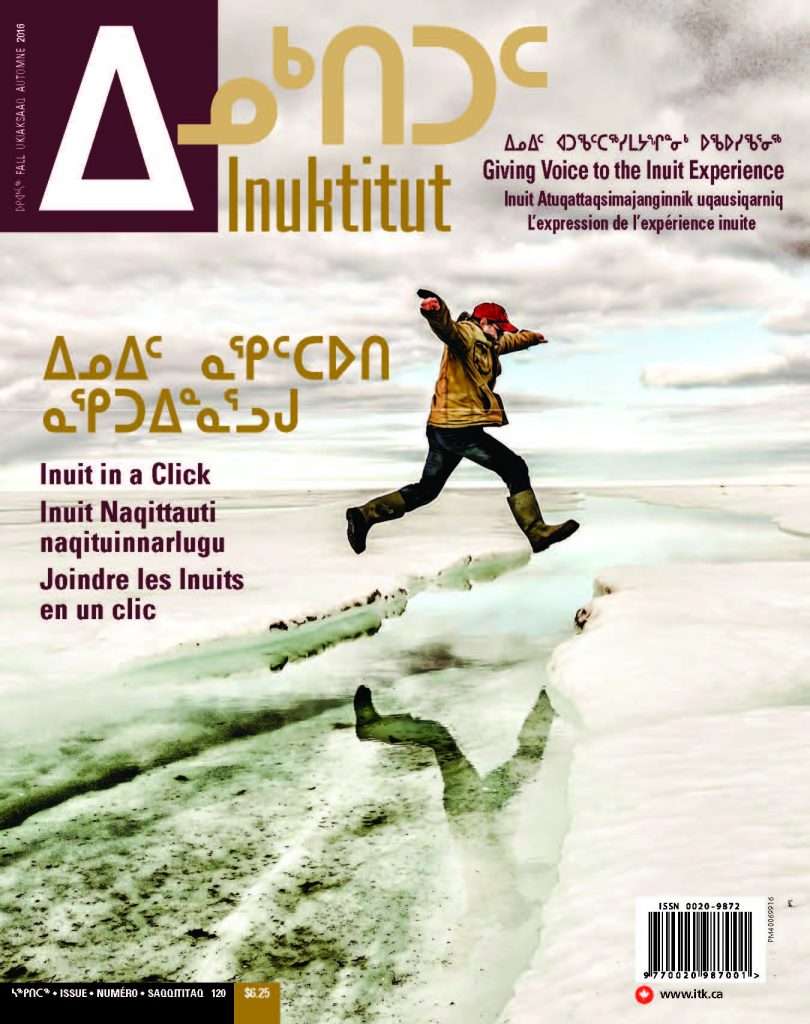

Her four children attended public school in Ausuittuq. She worked full‐time as an Inuktitut teacher beginning in the early nineties. However, hunting made up a significant portion of her family’s income. These are some of her favorite memories, nightly hunting trips out on the ice illuminated by the midnight sun. Iga, her husband, and children would load up the qamutik with the essentials: tea, palaugaaq, and tools for hunting and skinning ringed seal. Nattiq hunting provided much more than a steady income; the ringed seal was and continues to be a significant and rich source of nutrition for her family, supplemented by groceries from the northern co‐op store.

With the abundance and access to hunting and her teaching job, Iga and her family could enjoy holidays in western Canada. At the time, flights from Resolute to Edmonton were more affordable and more frequent due to the prosperous Polaris mine near Resolute bay. However, with the mine closure in the early 2000s, direct flights to and from Resolute airport were no longer scheduled. The sudden absence of transit workers traveling through Resolute meant airline companies would downgrade their fleet from 737 jets to much slower and smaller turboprop engines. This would not only affect leisure travel, but any medical travel, except emergency medical evacuation, would become an exhausting multi‐day journey.

Families in Ausuittuq, such as Iga’s, not only built a community, but they thrived during a period of significant political, social, and economic change in Nunavut. Following the momentous creation of the territory of Nunavut towards the end of the decade, Inuit felt the growing pains of a newly emerging administration. Creating a new, decentralized government meant communities experienced disproportionate impacts. Since the turn of the century, Iga has noticed her job as an Inuktitut teacher slowly recede from the primary curriculum. However, she knows that by returning to traditions, the land, and the language that carries, her family and her community will continue to grow stronger.