© Eric Boomer

Strength from the sled

IN THE VAST expanse of Nunavut, where the land stretches out like an endless white canvas and the sky meets the horizon in a seamless blend of blue and white, the tradition of qimussiq, or dog sledding, runs deep in the veins of Inuit. For me, learning to manage a dog team as an adult was not just about mastering a skill; it was a journey of reconnecting with my culture, finding my voice as an Inuk woman, and revitalizing a tradition that has been passed down through generations of my family.

Coming from a line of esteemed dog teamers, the legacy of qimussiq courses through my blood like a river flowing through the frozen tundra. My great-grandfather, Danish explorer Peter Freuchen, was a legendary figure in the world of Arctic exploration, his tales of adventure and survival inspiring awe and admiration in all who heard them. My grandfather, Ollie Ittinuar, carved out a life for himself and his family in the harsh yet beautiful landscapes of the Kivalliq.

Both men relied on dogs. And my father, Harry Ittinuar, continued the tradition and shared many stories with me about his time leading a dog team.

Despite growing up surrounded by the sights and sounds of qimussiq, it wasn’t until adulthood that I felt called to take on the tradition myself. As the first woman in my family to embrace this skill, I was determined to honor the legacy of those who came before me while forging my own path forward. With the guidance of team owners and mentors in Iqaluit, who shared their wisdom and expertise with me, I embarked on a journey of learning and self-discovery.

Learning to lead a dog team as an adult was not easy. It requires patience, perseverance, and a willingness to step outside of my comfort zone. Most importantly, it requires the ability to observe each dog individually, learning who they are and knowing their strengths, building the bond.

I remember the moment I knew I had built that connection with them: I was able to prepare the qamutiik, harness each of the dogs on my own, and take off on my own. On this particular run, I felt fully connected to the team, observing them and recognizing how my voice carried along the trail. Passing other dog teams is a challenge at times, and I was able to control the team with my voice and physically guide them around other teams. The dogs responded to me with no hesitation, and we successfully completed a 15-kilometer run.

With each passing day, I grew more confident in my abilities, drawing strength from the sled dogs that ran tirelessly by my side and the generations of dog teamers who came before me. As I navigated the snow-packed trails on the outskirts of Iqaluit, I found myself not only mastering the physical skills of dog sledding but also discovering a newfound sense of purpose and resilience within myself.

As a mother, I knew that it was important to pass on the tradition of qimussiq to my son, instilling within him the same reverence for our culture that had been instilled within me. Together, we embark on adventures across the frozen land, the sled dogs bounding ahead with joyful enthusiasm as we follow in their wake.

I watched as my eight-year-old son developed a deep connection to the land and the sled dogs, learning valuable lessons about perseverance, teamwork, and respect for nature along the way. Age 12 now, he jumps on and off the qamutiik, running, smiling and pushing with the team, realizing he is braver than he thought he was. A proud moment as a parent.

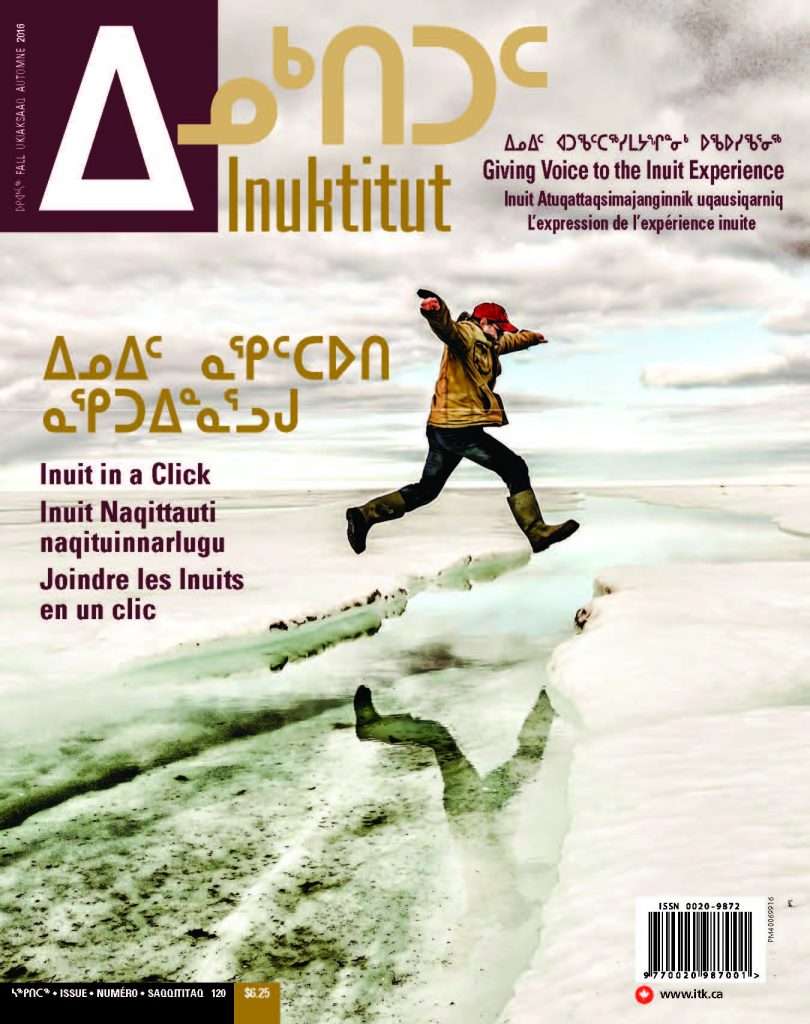

It runs in the family: Aglukark teaching her son to dog team. Aglukark’s father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all had dog teams

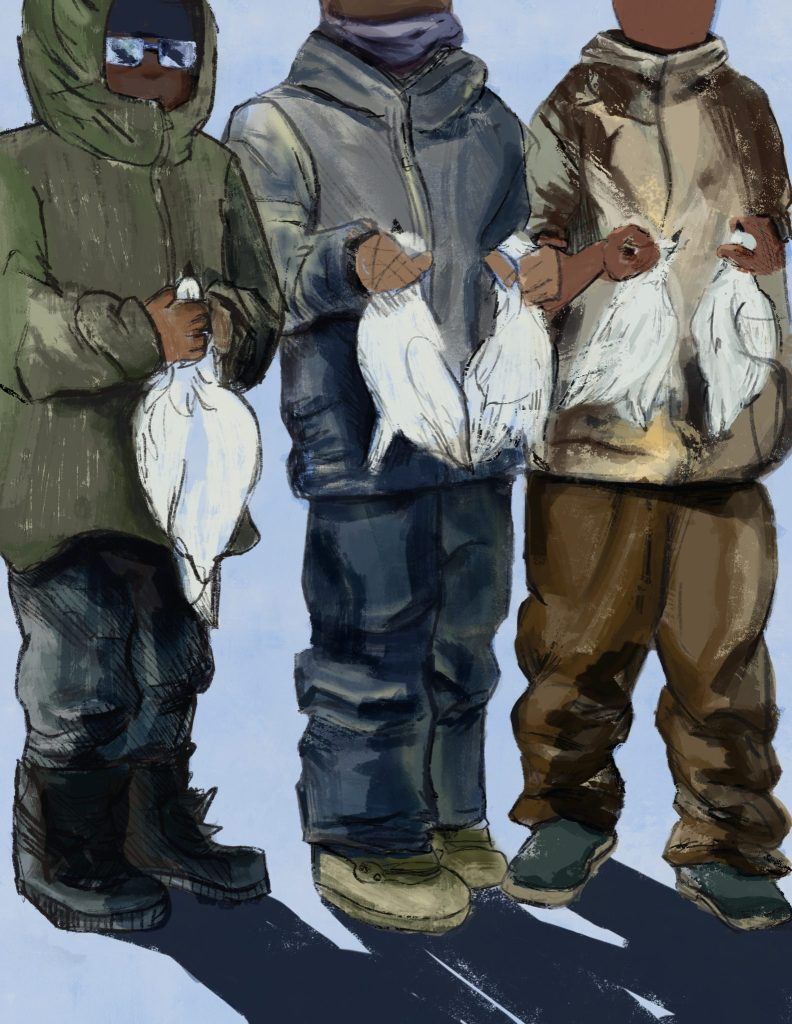

Leading a dog team requires patience, perseverance and a willingness to step outside your comfort zone, Aglukark says, and also the ability to recognize each dog’s individuality. © Eric Boomer

Revitalizing the tradition of qimussiq has been a labor of love for me, a way of honoring the legacy of my ancestors while paving the way for future generations. Through my journey, I have found my voice as an Inuk woman, speaking out against the forces that threaten to erode our cultural identity and advocating for the preservation of qimussiq.

During this journey, I was provided an opportunity to take part in promotional videos for companies such as Mustang Survival Gear, travelling by dog team to a nearby polynya; another with the Ski-doo company, showcasing the historical way of transportation by qimussiq and the modern way by snowmobile.

We also collaborated with the Telus World of Science Edmonton Museum for their exhibit Arctic Journey. On this journey, you can take a walk through Inuit Nunangat, and take a ride on a dog team through a 180-degree screen while listening to the sounds of the qamutiik gliding across the snow and the traditional calls we use today to guide our sled dogs.

“Revitalizing the tradition of qimussiq has been a labor of love for me, a way of honoring the legacy of my ancestors while paving the way for future generations.” © Eric Boomer

With each passing day, I am reminded of the profound resilience of our spirits, a resilience that has been shaped and strengthened by the timeless tradition of dog sledding.

Now, when I travel with the dog team through places like Tar Inlet, Qaumarviit Territorial Park, and Sylvia Grinnell Park, I do so with a sense of pride and purpose, knowing that I am carrying on a legacy that will endure for generations to come.

Aglukark was the first woman in her family to learn how to manage a dog team. © Eric Boomer