© Siku Rojas

On Seal Hunting and Archie Comics

An English Scholar Grapples with a Love for Written Words and a Heritage of Oral Education

I REMEMBER WELL the feeling the rugged land of home evoked in me at a young age. I had no tools then to convey this feeling, other than the word “cool.” In retrospect, I know that the warm greens of grass and lichen contrasted with the brilliant blues of sea ice just under the snowy top layer in a way that created a sense of forceful beauty. I’ve since fallen in love with being able to communicate those kinds of experiences, a passion that has led me to study English literature in university. I love how language, whether Inuktut, English, or any other, might capture what goes on in one’s head, when core memories are made, or remembered.

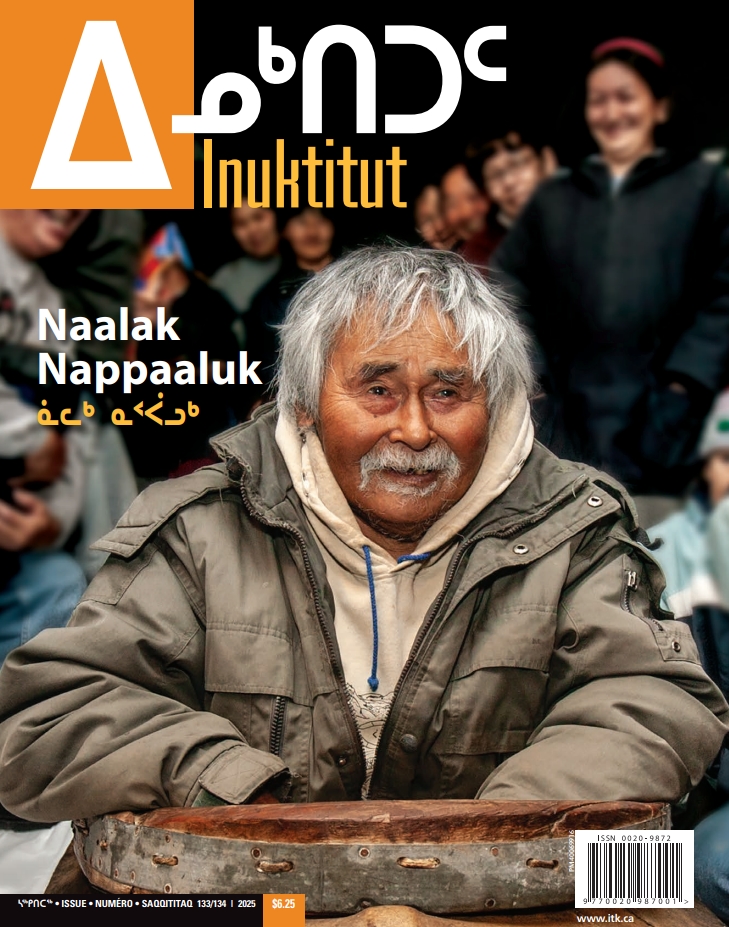

My name is Kyran Alikamik. I’m 21 years old and have lived most of my life in Ulukhaktok, in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories. My grandparents worked with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) for over two decades as seal monitors, taking frequent samples from baby and adult seals and shipping them out. Every summer, I camped 10 kilometres away from Ulu with my grandparents, in Mashuyak where we stayed in our family cabin. Those summers were some of the best of my life; it was just my grandparents and me alternating from the cabin to the water, from the water to the cabin. I helped my grandpa catch seals, and from him, I learned the intuitive skills of hunting on the boat. I watched what he did and replicated it to my own best ability. The days of being on the water, when I couldn’t discern where the ocean ended and the sky began, were what I looked forward to most; it was easy to see where a seal’s head would emerge. The sense of infinity this would evoke made me feel free and I had fun, save for the times I would miss a shot so obnoxiously that I had better chances of hitting a wayward seagull.

© Siku Rojas

The oral tradition is no less rich and full of particular wisdom than great stories like Beowulf or Plato’s Republic.

When I look back to those countless hours spent on the boat, I admire the knowledge my grandparents transferred to me. At no point had they explicitly broken down in steps how to do what they did. Through this knowledge transfer, I recall a connection to my culture and land utterly different than any formal education could provide. The learning I engaged in at Mashuyak and on the water was instinctive and physical. I needed both kinds of learning to become the person I am today.

Those summers ended with the first day back in the classroom and, as I approached high school, my interest in English language arts courses became clear. I had a natural affinity for English, and a great love for reading fiction, my first obsession outside of school being Archie Comics. I read them and reread them and reread them again. My developing passion for English began to take flight in Grade 10 when one of my teachers placed a few students in an enriched reading program, including me. We read and analyzed the science fiction novel Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card. We also read publications by former Canadian senator Roméo Dallaire detailing the realities of child soldiers. Through this reading program, I felt the impact literature can have and its importance in advocacy and current affairs, outside of being a mere pastime. In looking to the future for what my career was to look like, I saw English as the end‐all‐be‐all. This was to be my thing. That is the primary reason I attend the University of British Columbia to study English literature. Now, going into my third year of an undergraduate degree, I have been reflecting on what my education means for me and how it influences me. I am enamoured by the Homeric epics, emotionally attached to the works of Shakespeare, and invested in Eastern works like the Bhagavad Gita. Pieces of art such as these have shaped my intellectual development and have changed my worldview. Yet, as I moved through high school and university, I could never shake the feeling that something was missing. It’s obvious to me now this was caused by the gap between my western education and the learning style that is foundational to my past, my family history, my Inuvialuit culture. The path of my career, and what I need to learn and apply to follow that path, leaves little room for the type of learning I did with my grandparents, one that defined much of my childhood.

© Siku Rojas

During an Eastern Philosophy class on a foggy and wet morning at UBC, I was sipping on my coffee and had a Eureka moment. The class discussed an ancient text called the Vedas, written more than 3,000 years ago. I remember comparing Inuit culture with what the Vedas represented as a story, and as a great repository of knowledge about old ways of life. As I looked up at the less‐than‐functional off‐white ceiling fan in thought, I wondered about the kind of passion I would have if I were to study Inuit history in this way. Then I realized that I couldn’t, potentially ever.

My grandpa didn’t learn the weather patterns, and how to harpoon a beluga and what hilarious, amazing stories to tell, by reading some book called “On the Migration of Geese” or “How to Tell Stories and Influence People.” The transfer of knowledge, stories and lessons in our culture and history is almost entirely oral. Only in the last few decades or so are we seeing efforts to capture the Inuit way of life on the page. The oral tradition is no less rich and full of particular wisdom than great stories like Beowulf or Plato’s Republic; it just takes a different form. This of course means, with this oral nature, that we don’t—I don’t—have ready access to stories and lessons of old to study and muse over.

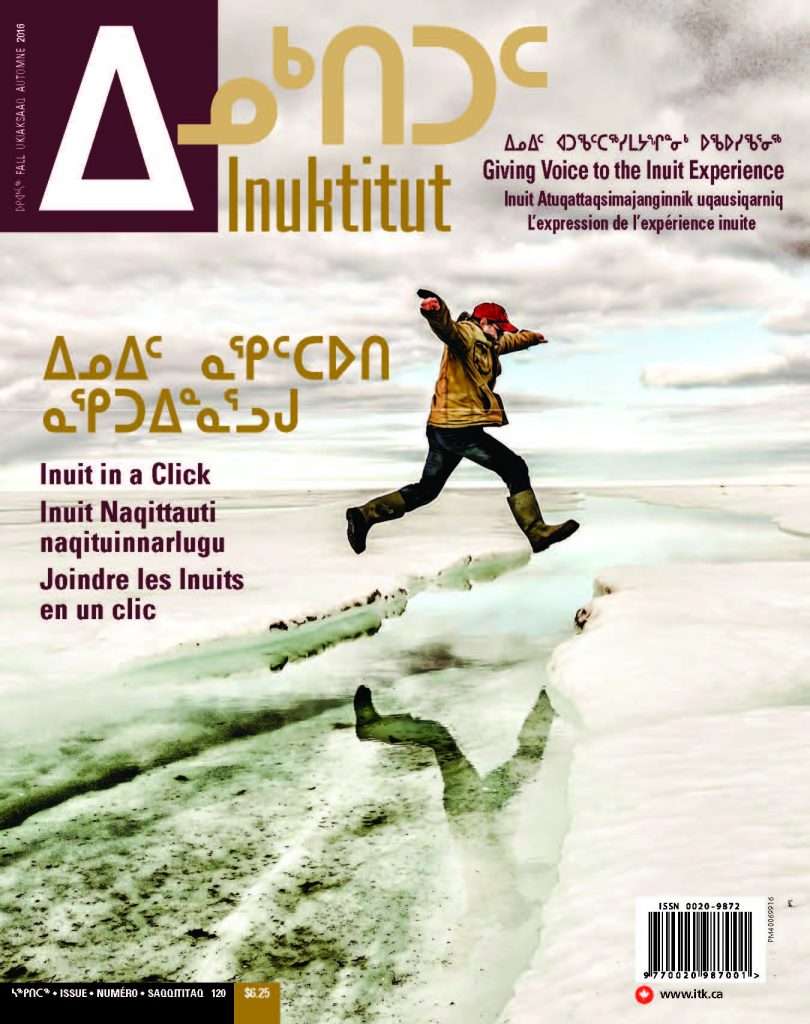

Alikamik’s grandparents outside their cabin in Mashuyak, a town campsite about 10 km away from Ulukhaktok. © Siku Rojas

Being steeped in a primarily Western lens and academic tradition these days, as any other Inuk might find in this route to a career, means it becomes harder to access our collective well of culture and history. Yet, that makes it all the more important to sit down and ask our grandparents and other community members, with great interest, what stories they have to tell. We have the express opportunity to make our cultural history accessible in other ways for future generations, and I believe that’s wonderful.