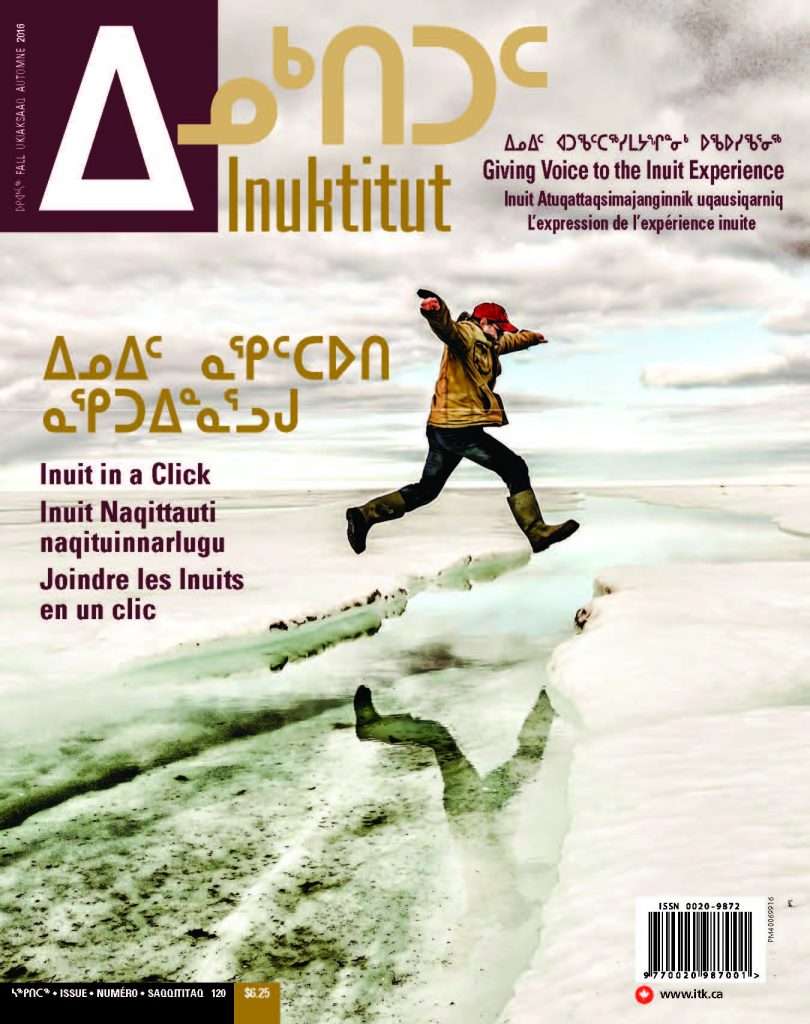

Sandi Vincent in Iqaluit. © Qaggiavuut

Live by the Drum

AS A DRUM DANCER LIVING IN IQALUIT, with family roots in Iglulik, I am most familiar with traditional drum practice of the Nunavut area, which usually entails a man composing his own song, and his wife and family singing while he drums. One song many Nunavummiut may be familiar with, Anirausilirlanga, is about when two specific stars become visible again, signifying the imminent return of the sun after the season of 24‐hour darkness.

I feel humbled to have been entrusted with songs and stories and am driven to do my best to share them in my community, territory, country and throughout the world. I was honoured to perform this piece by composer Ootoova from the Mittimatalik‐area known today as Pond Inlet, when I travelled to Greenland to attend a drum dance festival in March 2022 with the support of Nunavut’s Qaggiavuut Society for Performing Arts.

I was part of a small group of Canadian Inuit cultural performers travelling for the Katuarpalaaq Drum Dance Festival in Nuuk, Greenland. This year the festival would celebrate an international honour: the inscription of Inuit Drum Dancing into the United Nation’s Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This international list recognizes and encourages dialogue about diverse cultural practices and expressions of humanity.

I feel so much pride in Inuit, especially when I am able to share aspects of our culture with those who appreciate it. I realize that I will one day be an Elder, and it will be my duty to pass on what I have learned from many Inuit more knowledgeable than me, and I feel motivated to absorb and understand as much as I can. I think of traditional camp life, and how Inuit would follow animals and seasons, how community members would only bring necessary items, and that a drum was considered necessary—it still is.

Sandi Vincent performs at the Katuarpalaaq Drum Dance Festival in Nuuk. © Qaggiavuut

When our group arrived in Nuuk, there was excitement in the air. The event, which had been disrupted for several years due to COVID‐19, was a much‐needed opportunity for the city to gather and welcome visitors once again. Over the coming week we would join Inuit drum dancers from across Inuit Nunangat to practice and to celebrate both our shared and unique styles of drum dancing from Canada, Alaska, and across Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland). Just as there is a difference in drums and drum dancing between the Eastern and Western Arctic in Canada, there is a difference across Kalaallit Nunaat as well. For example, Greenlandic drums are still made with skins and need to be moistened before using.

We led and participated in drum dance workshops performed at pop‐up events and prepared for the festival’s final collaborative concert. Throughout the festival we created this performance, showcasing different performers and styles, incorporating katajjaq, or throat‐singing, Uaajeerneq, or mask dance, and even the use of a loop pedal which was shared with a full house.

In the workshops, we discussed the importance of drum dancing, what it means to us, and what we see the drum as a tool for. Personally, I have leaned on throat‐singing, drum dancing and drum songs called pisiit to learn more Inuktitut, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, Inuit stories, and to strengthen my Inuk identity. Being grounded in a sense of self and sharing an identity with my Inuuqatiik gives me a sense of belonging and a source of resiliency to draw from. When I attended the Nunavut Sivuniksavut Training Program in Ottawa, I was able to build my own drum with celebrated drum dancer David Serkoak. When I participated in the Nunavut literacy non‐profit Ilitaqsiniq’s sewing skill program called the Miqqut Project, I was able to learn about the pattern pieces and the animals that are represented by them and sew my own tuilii (an amauti made with large shoulders for carrying newborns) with guidance from Rankin Inlet Elder Maryanne Tattuinee. I was proud to bring both pieces and use them in our performances. Over time, learning the complexities of the history, terms, symbolism and stories behind songs, dances, clothing and tools has shown me the deep thinking, respect for environment, and ingenuity of the Inuit who came before me.

At the festival, our group also sang a song we learned from Susan Avingaq of the Amiituq‐area, or Igloolik, which had come from the Salliq‐area, now Coral Harbour. This song was composed by a hunter walking alone with his dog who is helping him find seal holes. The hunter is struggling to find the words for his song because his Elders have taken all the words, but he is singing about what he caught, a bearded seal and a caribou. How lucky we were that Avingaq learned this beautiful song and was generous enough to share it. I have been able to reflect on how important it is to know these old songs, and to understand the special terms used in pisiit that are not used in conversation, like words describing animals or tools.

Sandi Vincent performs at the Katuarpalaaq Drum Dance Festival in Nuuk. © Qaggiavuut

Elder Inukitsoq Sadorana of Qaanaaq, in Northern Greenland, shared with our group a family song that came from his father and grandfather. As he drummed, his wife Genoveva sang and twirled a small ivory amulet. At the end of the pisiit there is a way to thank the composers of the song and give appreciation and recognition to them. Nuka Alice Lund of Sisimiut shared songs she had composed, and the journey she has been on to reclaim and revive drum dancing. Being able to share the stories behind the songs with other drum dancers opened the door to the conversation of family songs, personal songs, and collective songs. I compare these different types of drum songs, including who sings them, to sewing patterns. There are some patterns people willingly share, to help introduce patterns and techniques so they can live on into the future; and there are some patterns and styles that seamstresses are known for, and sharing is limited to familial and personal ties only.

Our stories, our language, our history and our respect for animals and environment are embedded in the arts. The arts, especially performing arts, are a great tool for language revitalization and cultural re‐connection.

We all turn to the arts—whether we are makers or consumers —through songs and music; storytelling, including movies, television and theater; art made by hand such as prints, beaded and sewn items, and carvings. It is a way to connect with a bigger community, express ourselves and our emotions, reflect on our environment, and to share lessons. That week in Nuuk, the Katuaq Culture Centre was the epicenter of arts, and a place for community members to make and appreciate art, and all that it offers. We are only able to celebrate the continued practice thanks to our ancestors whose collective songs we have learned—and to move forward, by creating new songs and ways of performing.