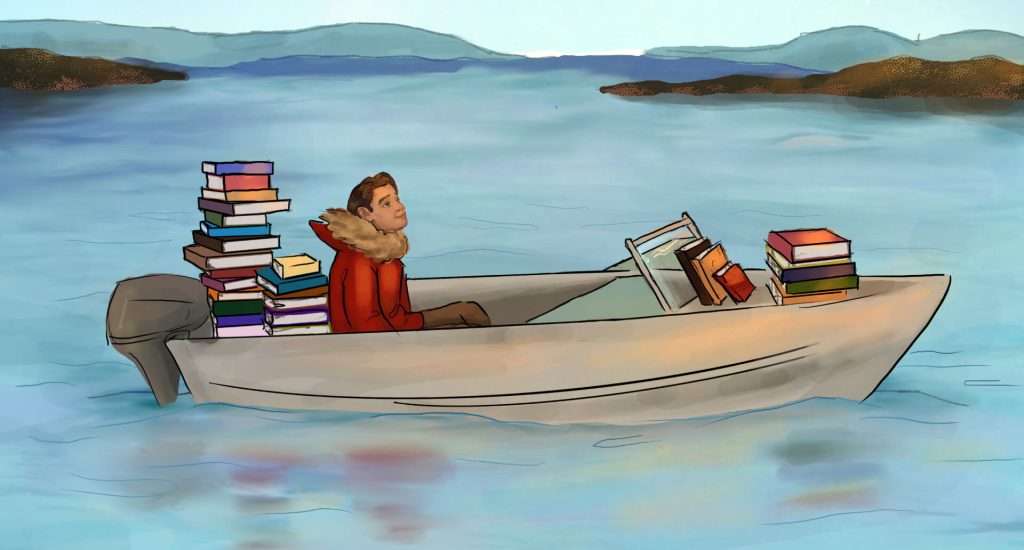

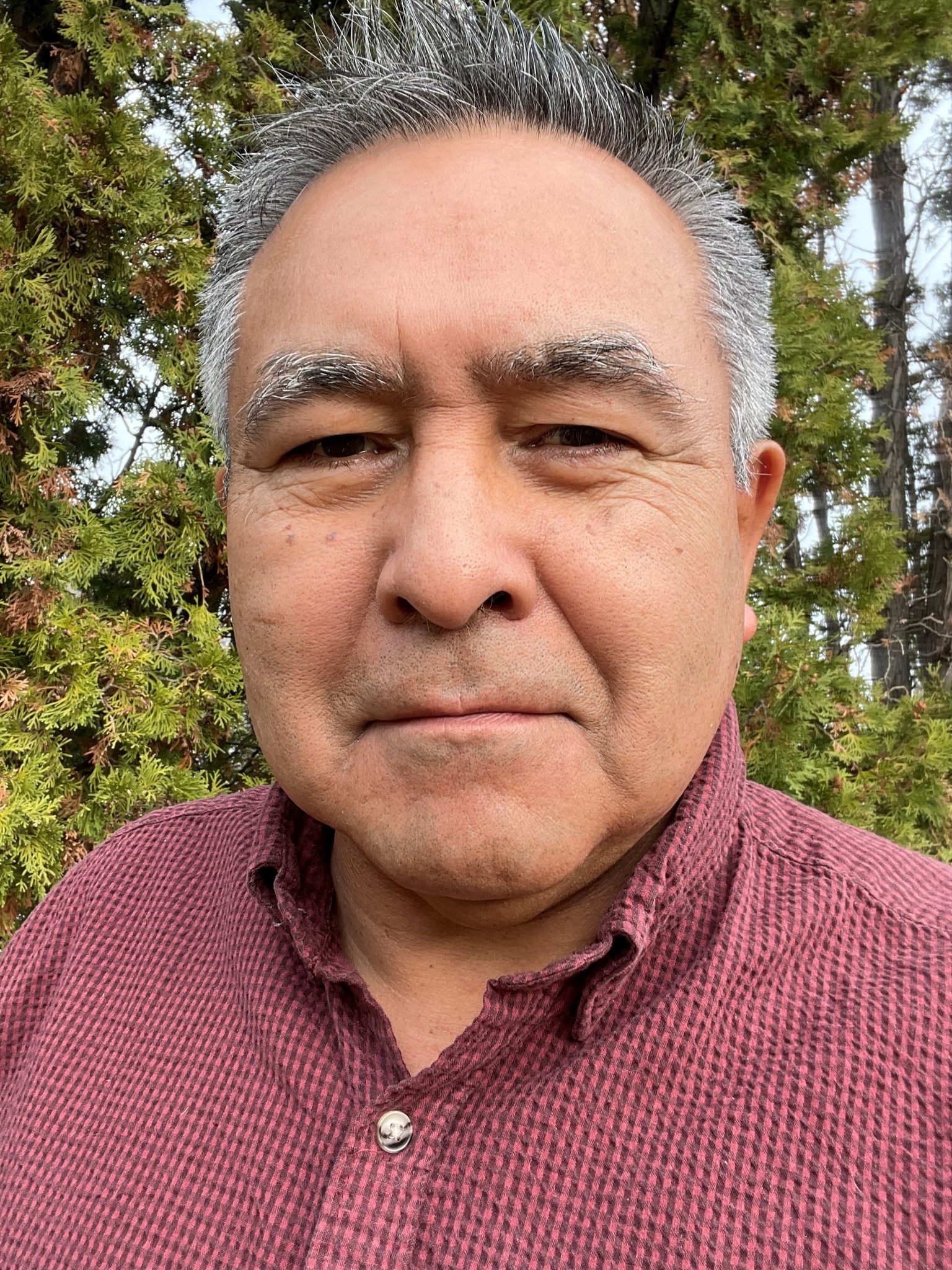

Dennis Allen performs for a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation event in Edmonton on September 30, 2023. © Darlene Hildebrandt

Finding Your Voice

IN THE 1960’S, Gwich’in Elder Edith Josie of Old Crow, Yukon, would write a column for the Whitehorse Star called, “Here Are The News.” She reported on the comings and goings of her tiny, isolated village. She wrote about what was important to her: who killed caribou, who went trapping for the fall, who died, who had children, who got married, everything to do with community life. The newspaper’s editors were so enamored with her writing that they didn’t change any of her stories. They let her speak in her own voice, hence the title, “Here Are The News.” While Edith wasn’t a trained writer, her columns were genuine and heartfelt. She became so popular that her column was syndicated by big newspapers. To the mainstream media, an Indigenous Elders’ perspective was fresh, exciting, and full of emotion.

A good friend of my grandmother, Josie would visit my family when she came to Inuvik and bring her stories too. I am Inuvialuit and Gwich’in, and my family ties are in Inuvik, NT. Whether it is through short stories, songwriting, or film, I try in my work as a writer to give my reader a true perspective of Inuit life and identity. As Inuit, our customs, traditions, beliefs, and values were handed down to us from generation to generation through storytelling. Inuit are an oral culture. We mastered the art of storytelling because it was a matter of survival. Stories contained everything pertinent to our culture. A simple after-supper story would convey important information such as genealogy, geography, archeology, history, myths, skills, knowledge, and beliefs. I used to listen to my parents tell stories about traplines and dog teams. They told stories about Elders, whom I never got to meet, and how everyone was related. Through those stories, I learned who I was related to, where there were good trapping areas, and which way the caribou migrate in the fall time. I’ve taken to writing those stories down. I’ll share one story from when I grew up that was shared with me.

My dad’s grandfather on his dad’s side was Allen Okpik. Okpik and his wife Eileen were Nunatakmiut from Alaska, inland caribou people from around Anaktuvuk Pass. In the late 1800s, the caribou migration routes changed and there was a big famine in that area of Alaska. The Nunatakmiut were left to live on ptarmigan, rabbits, and fish. It was not enough to sustain the entire tribe, and the majority of families began a trek toward the Arctic coast in hopes of securing food from the newly arrived traders. When they got to the coast however, the traders had barely enough food to survive themselves. Several families turned around and went back, others stayed and settled there, and others kept walking westward toward Canada. They had heard of trapping grounds, rich with muskrat and white foxes. When they arrived, indeed there were rich trapping areas in the Mackenzie Delta and along the coast. In a short time, Allen Okpik, along with his five sons, made enough money from trapping furs to buy a schooner, the Arctic Bluenose. Okpik then sailed back to Alaska and picked up his two brothers, Angik Ruben, and Garrett Nutik, who had settled on the coast. He brought them to their new home in Canada’s Western Arctic. A good portion of the Mackenzie Delta Inuvialuit are descendants of those first families who came west.

For a long time, Inuit stories have been written down by non-Inuit. But those many books, movies and magazines share only a limited perspective. It is impossible for them to capture all the intricacies of Inuit existence when the writers do not share our beliefs, customs, traditions, and ways of life. Last winter, a group of Inuit writers gathered in Iqaluit for a circumpolar writer’s festival called Titiraqtat, held by the Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada. I spoke to participants about the importance of writing in their own voices, and the value of writing that reflects our Inuit identity.

Inuit culture is rooted in communal values like sharing, the land, animals, family, and community. For our ancestors, if we did not share, people would die. If we did not value the land, we would have abused it. If we did not value the animals, they would be extinct. If we did not value family, we would be alone. If we did not value community, we would have no society. These values drove us as Inuit. They defined us. To find our voices as Inuk writers, we need to allow those values to drive our writing too. We can do this by drawing on the Inuit tradition of oral storytelling and write like we’re talking to one another. Write like we think, speak, feel and exist. What is important to me? What defines me as an Inuk? I write to answer these questions. I’m reminded how Edith Josie told her stories, and how they resonated with people. But Edith didn’t care what other people thought about her writing, or her language, or her community. She was writing for her own people. I encourage you to do the same.

Dennis Allen performs for a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation event in Edmonton on September 30, 2023. © Darlene Hildebrandt