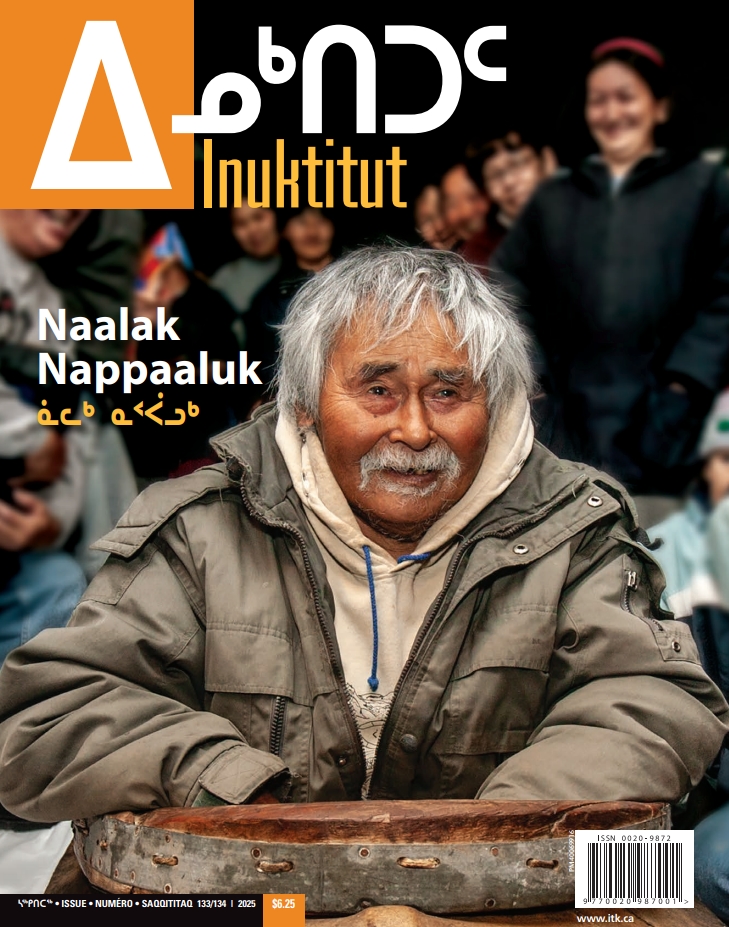

Beverly Lennie, Nanilavut project manager for the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, speaking at a Nanilavut public meeting March 9 in Aklavik. © Elizabeth Kolb

A Year of Searching

Nanilavut Continues Growing... and Finding

JEANNIE ARREAK-KULLUALIK knows the pain of not knowing. Her grandmother and grandfather boarded the C.D. Howe medical ship in 1950s in Pond Inlet, and travelled south for tuber culosis treatment. They never came back.

“I grew up with my mom always kind of searching for her mother,” says Arreak‐Kullualik.

In the 1980s, Arreak‐Kullualik’s mother, Koonoo Eunice Arreak, joined a group of Inuit who pushed politicians in the Northwest Territories to help find information about loved ones lost during the tuberculosis epidemic between the 1940s and 1960s.

Through that process, Arreak eventually found her mother’s final resting place in a cemetery outside of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

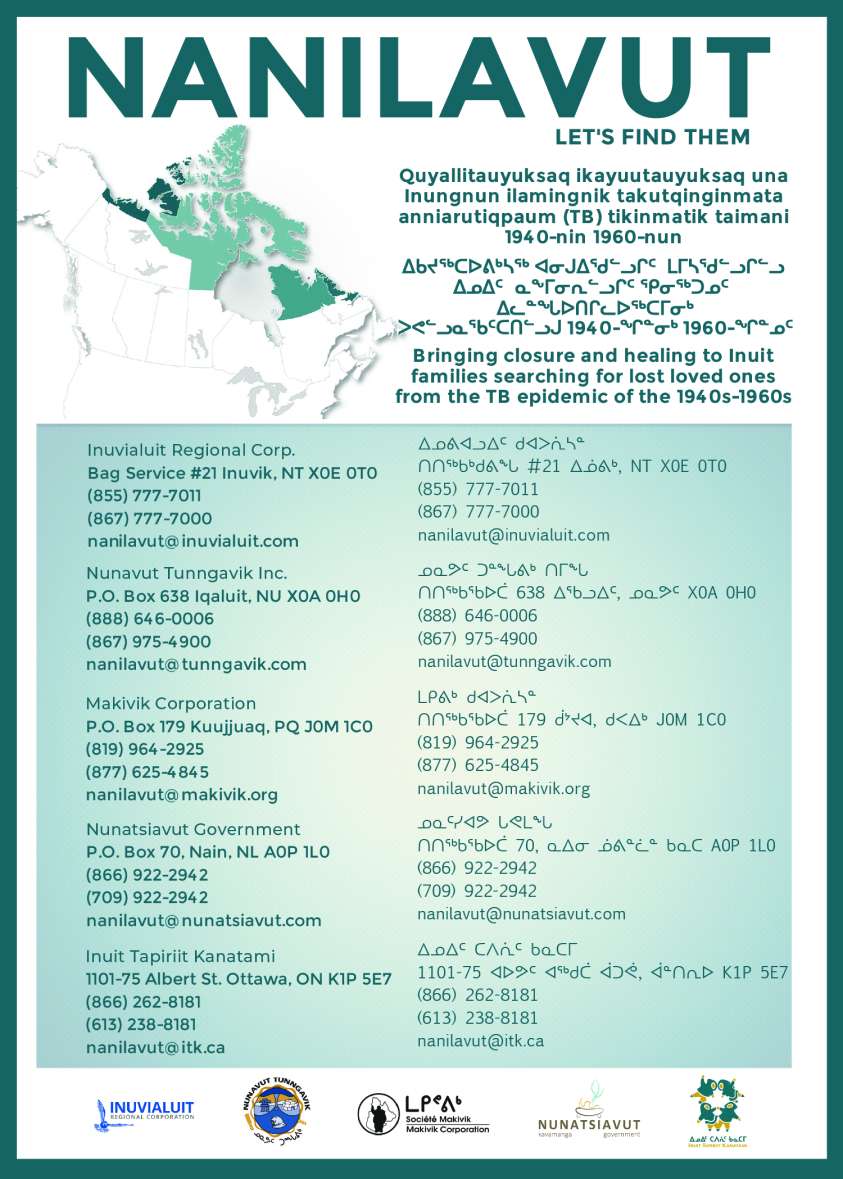

Arreak‐Kullualik, now working for Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, is continuing her mother’s work. She’s one of the originators of the Nanilavut initiative — a project that helps find information, bring closure to families, and discover the gravesites of Inuit forcefully sent south for tuberculosis treatment during the epidemic. Nanilavut means “let us find them” in Inuktitut. Many Inuit who left for treatment didn’t return home, and many of their families are still, today, searching for answers.

I was sitting there, crying,” says Ford. “They weren’t people that I knew, but they were my people anyway.”

“I was passionate about being involved with Nanilavut because I saw it first‐hand,” says Arreak‐Kullualik. Nanilavut was launched in March of 2019 following an apology from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for the mistreatment Inuit were subjected to during the TB epidemic.

Since the launch, the search for the missing has been tough. In some cases, Arreak‐Kullualik says families can’t provide much more information than their lost loved one’s name, or whether they were taken away by ship or airplane. Even for families who know where their loved ones were taken, the search is rarely straightforward. Names were often misspelled, and records are difficult to track down says Beverly Lennie, a Nanilavut project manager for the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. It can take months to confirm details that could lead to an individual’s final resting place.

© Melo Sammurtok-Lavallee

“You have to go through pretty much each person’s file and the year they were deceased,” Lennie says. “It is a lot of tedious work, but in order to get it done properly, you just have to take it one paper at a time.”

Although searching is tough, the hope is that more searches leads to more information for other families, too. The project includes a genealogical database that is constantly being updated as researchers find more records. Nanilavut is approaching 30,000 records in that database, with more than 4,500 names and pieces of information having been logged.

If a person or family wants to submit an inquiry to Nanilavut, first they must contact their regional Inuit organization’s Nanilavut project manager. The project manager searches for the lost relative’s name in the database. If nothing comes up, the project manager will search other archives, like territorial and provincial archives or church and cemetery records. If they’re lucky, they will find a document that offers a clue that leads to another record, and, eventually, the location of their gravesite.

If the project manager finds where the individual is buried, and are satisfied they have the right person, they arrange a meeting with the family. Joanasie Akumalik, project manager for Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, said he will never forget the first time he told a family that their loved one had been found.

“I was shaking a little bit because I was wanting to provide the information and have a sense of closure for those people,” he says.

“It’s very touching. We call the family to come to our office and we meet with them privately. We have an official letter with us both in English and Inuktitut and then we provide all the necessary confirmation documentation so that we can be sure that is the right person that we’ve found.”

It’s a powerful moment when families find their loved ones. But the emotional journey for project managers starts long before that. Listening to the stories of the families, which are often traumatic, and combing through death records takes a strong emotional commitment.

Cathy Ford, a Nanilavut project manager for the Nunatsiavut Government, recalls the first time she searched the archives at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland. After she began scrolling through Moravian Church records on rolls of microfilm, tears began rolling down her cheek.

“I was sitting there, crying,” says Ford. “They weren’t people that I knew, but they were my people anyway.”

Witnessing cemeteries where Inuit were buried, but without any markings on their gravesites, is one of the most difficult aspects of the job for Beverly Lennie.

“When you go to a cemetery, you expect to see where someone is buried by their headstone,” she said. “And to come across emeteries that have no grave markings at all, it has an emotional impact on a person.”

Although the work is draining, Joanasie Akumalik says his wife gives him the strength to continue.

“She suggested finding a grave will allow the soul of the person to be released from the Earth,” he said. “So that kept me going to this very day. It kept me going.”

To find out more about Nanilavut, contact your regional Inuit organization.