Cutting the sealskin rope to open the new community gym. From left: Mayor Billy Cain, Willie Cain Jr., Annie Kaukai, James May and Mary Cain. © Mikhaela Neelin

Building Nunavik

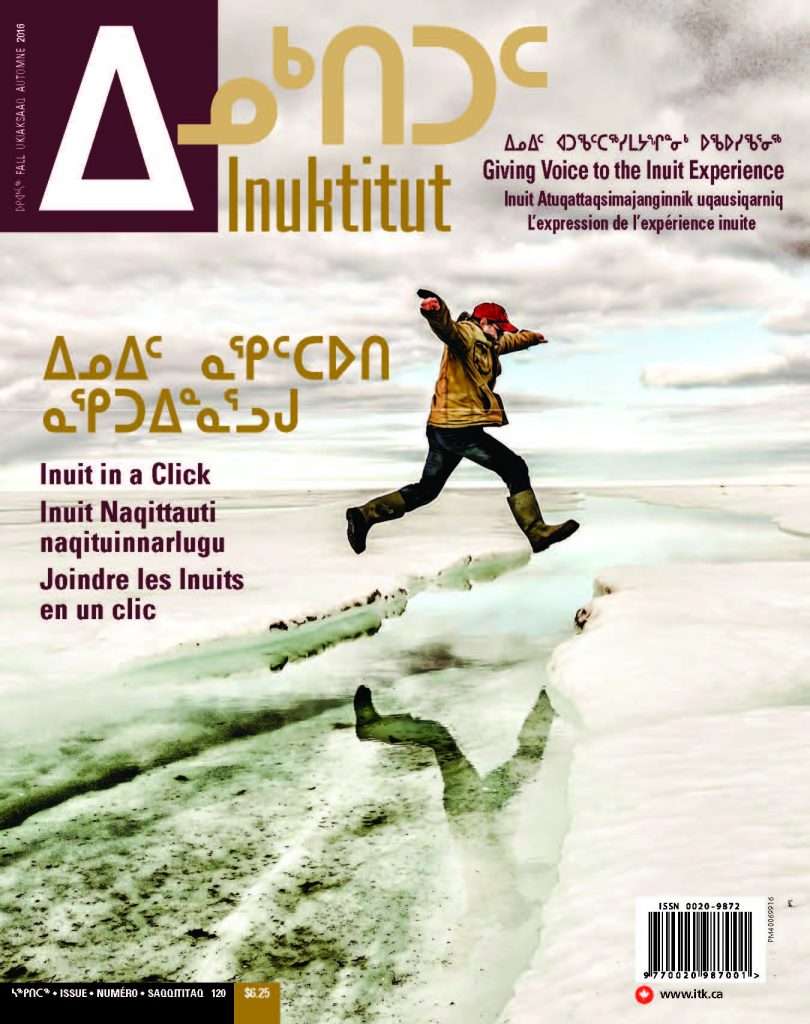

Tasiujaq sportsplex shows critical need for social infrastructure investment

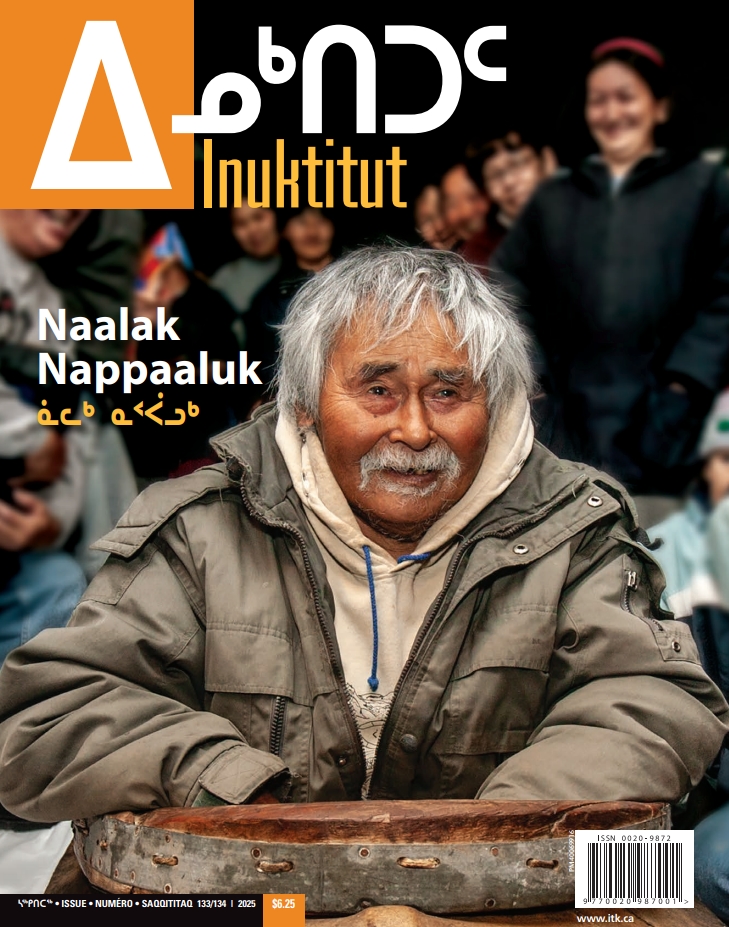

WHEN SCHOOL STARTED this fall in Tasiujaq, Nunavik, students couldn’t use their gym because of mold removal work. Like in many Inuit Nunangat communities, indoor public space is limited, so it was a huge relief for the village when a new community sportsplex opened in time for back-to-school activities.

Construction of Tasiujaq’s community gym—which includes a full kitchen, washrooms with showers, and a multipurpose meeting room—was finished in April 2024. It was the first building constructed in a Nunavik community under the Indigenous Communities and Infrastructure Fund, a federal investment, which allocated $517.8 million over 4 years in infrastructure grants for Inuit-specific projects in Inuit Nunangat.

Tasiujaq Mayor Billy Cain in front of the new community gym. © Mikhaela Neelin

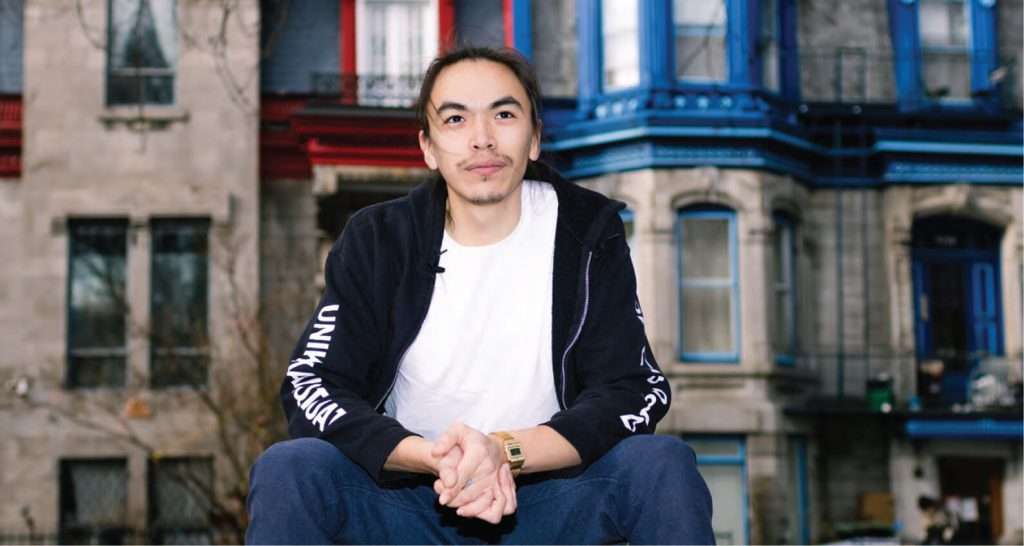

“We opened it as soon as it was finished,” says Billy Cain, Mayor of Tasiujaq and President of the Board of Directors for the community’s Arqivik Landholding Corporation. “We didn’t want the kids, teenagers, adults just to wait and not do anything. Today, they’re playing mostly volleyball. It’s pretty popular. They start around 9 pm and stop at 11 pm. Before that, the younger kids are playing soccer, floor hockey, basketball, what they want to do.”

The village has about 400 people and the sportsplex can hold about half that so the sportsplex will also be used for public events and feasts. The new gym fills a gap in the community, after Tasiujaq’s other municipal gathering space was damaged by fire in the spring of 2023.

When Makivvik, Nunavik’s Inuit Treaty Organization, was distributing the region’s $129 million portion of the infrastructure fund, the only requirement was for communities to put the money towards social infrastructure, says Vanessa Doig, Assistant Director to the President’s Department at Makivvik. “A lot of the funding that we tend to receive is for traditional infrastructure, like roads and municipal infrastructure,” says Doig. “There are not very many programs that come along for social purposes. Something like an arena or a youth house, those things are not necessarily priorities of large funding programs.”

Makivvik wanted to ensure this money benefited all communities and was not used for infrastructure that was already a government responsibility. As mandated by Makivvik, the ICIF funds were divided evenly between the region’s 14 communities for local, self-determined projects. That split gave $9 million to Tasiujaq for the new sportsplex.

It’s a beautiful new building—and just what the community asked for when they were polled over local radio. And yet, it still fell short of expectations, lacking enough money to include the workout centre, full change rooms, and movie theatre that the municipality wanted. “In today’s market the supplies are so expensive. We didn’t get everything,” says Cain. “Out of what we requested, we got the kitchen for a canteen, the conference room to have meetings and the washrooms with showers,” as well as the gym.

While the sportsplex was 100 percent federally funded, the village and landholding corporation will need to budget their own money to maintain the new sportsplex. “It’s the operational funding that will be challenging because we have to pay for the workers there,” says Cain. “A coordinator, janitors, expenses for municipal taxes, unforeseen expenses.”

To manage infrastructure funding in the region, Makivvik set up a new division with a designated project team to take applications and support communities from the idea phase through to construction. The project team includes engineers, construction experts, and project managers. Four-year federal funding cycles for capital projects can make construction timelines tight so Makivvik helped to speed up the process by using its own construction company, Kautaq, which works exclusively in Nunavik. “ICIF was announced in Budget 2021, in April,” says Doig. “We didn’t learn about the Inuit allocation until August, and at that point we had missed a sealift. So, all of a sudden, we have $517.8 million for Inuit Nunangat and only a handful of sealifts to get all of that infrastructure into the North.”

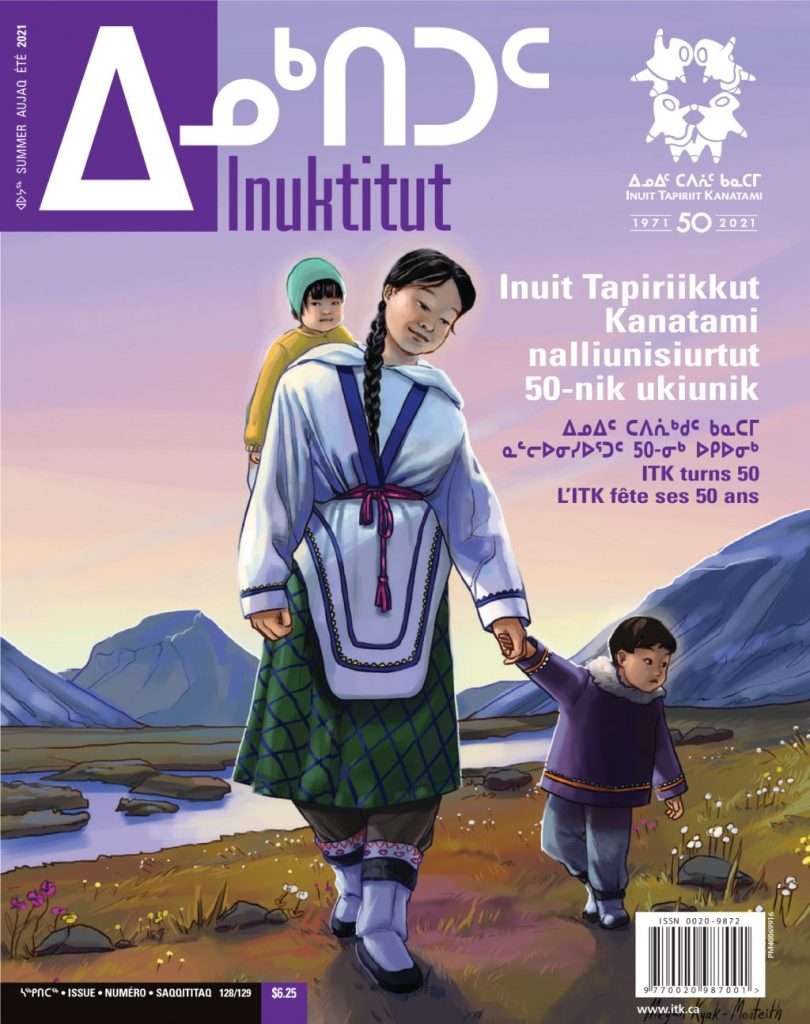

Inside view of the new community gym. © Mikhaela Neelin

Throughout Inuit Nunangat, more than half of the Inuit infrastructure program money was spent or committed as of April 2024, with one year left in the program’s funding cycle, according to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami’s mid-term review of the Infrastructure Canada Investment Fund. But in that same review ITK’s infrastructure team states this one-time funding, “while an important step,” is “unlikely to significantly narrow the infrastructure gap between Inuit Nunangat and the rest of Canada.” In a 2022 assessment of the infrastructure gap in Inuit Nunangat, ITK and local community organizations found it would require an investment of $55.3 billion into roughly 115 capital projects over the course of a decade to see this gap truly addressed. And that calculation doesn’t even include annual operations and maintenance costs.

“Infrastructure deficits in Inuit Nunangat drive many of the social and economic inequities experienced by Inuit,” the assessment states. “The 51 communities in Inuit Nunangat struggle with infrastructure deficits in all sectors, including in the areas of telecommunications infrastructure, transportation infrastructure, and social infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, and shelters for vulnerable populations. To close the infrastructure gap between Inuit Nunangat and other regions of Canada, the ICIF must extend beyond the current four-year timeframe.”

Accordion player David Angutinguak was one of the first to perform at a concert and dance at the new gym. © Mikhaela Neelin

In the meantime, communities are taking advantage of the ICIF, which Doig calls “one of the most flexible federal programs” that Makivvik has ever worked with. “The only major requirement is that it closes the infrastructure gap, which is up for interpretation, but in a positive way,” she said. As of summer 2024, nearly 90 percent of Makivvik’s ICIF funding was committed, with every community having completed plans to use either all or more than 60 percent of its funds. Besides two other sportsplexes like the one in Tasiujaq, the money is going towards projects such as youth centres, workshops for carpentry and skidoo repair, arena upgrades, community centre expansions, and playgrounds.

“It was very much a discussion of ‘what can we do that the people will benefit from?’ Roads, yes, those are important,” says Doig. “But where do the children play? Or where does the community gather? Those are the priorities that we need to set as well.”

Tasiujaq children enjoy a candy drop at the opening of Tasiujaq’s new gym. © Mikhaela Neelin