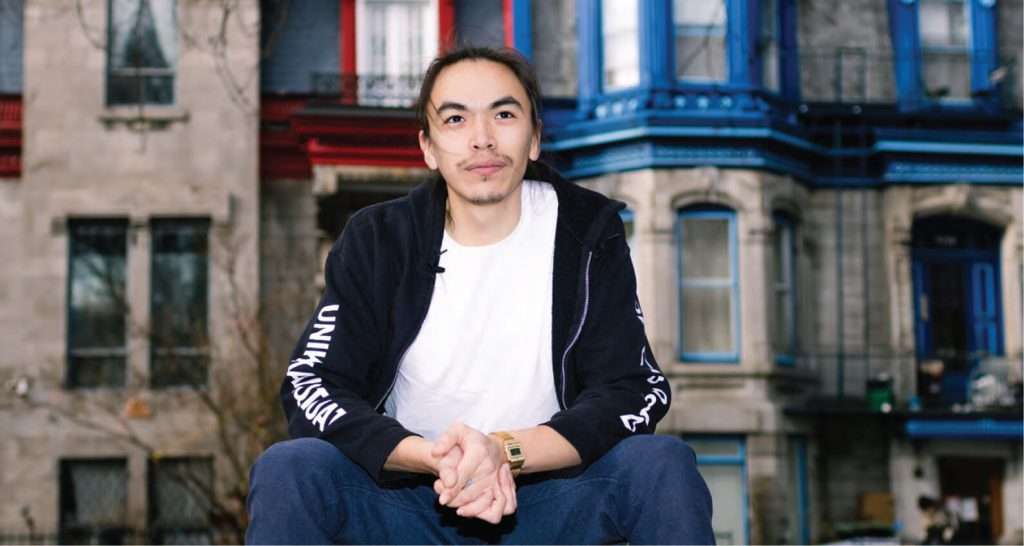

Naalak Nappaaluk in October 2004, celebrating the return of the last traditional qajaq to be made in his hometown of Kangiqsujuaq, Nunavik. The qajaq was repatriated from the Musée de la civilisation de Quebec and is now displayed at the Pingualuit National Park Interpretation Centre. © Robert Fréchette

Return to the Sea

BEFORE HE DIED IN 2010, Naalak Nappaaluk loved being on a boat at sea, hunting beluga. The Kangiqsujuaq elder always brought a gun, but he preferred using his unaaq (harpoon), especially for bearded seal, says his daughter, Qiallak Nappaaluk. He liked being close to the seal, the physical effort it took to pull the seal in, and the knowledge that the embedded head of the unaaq would ensure the animal did not sink down out of reach.

Naalak’s spirit will soon return to the sea, and to the service of all Canadians.

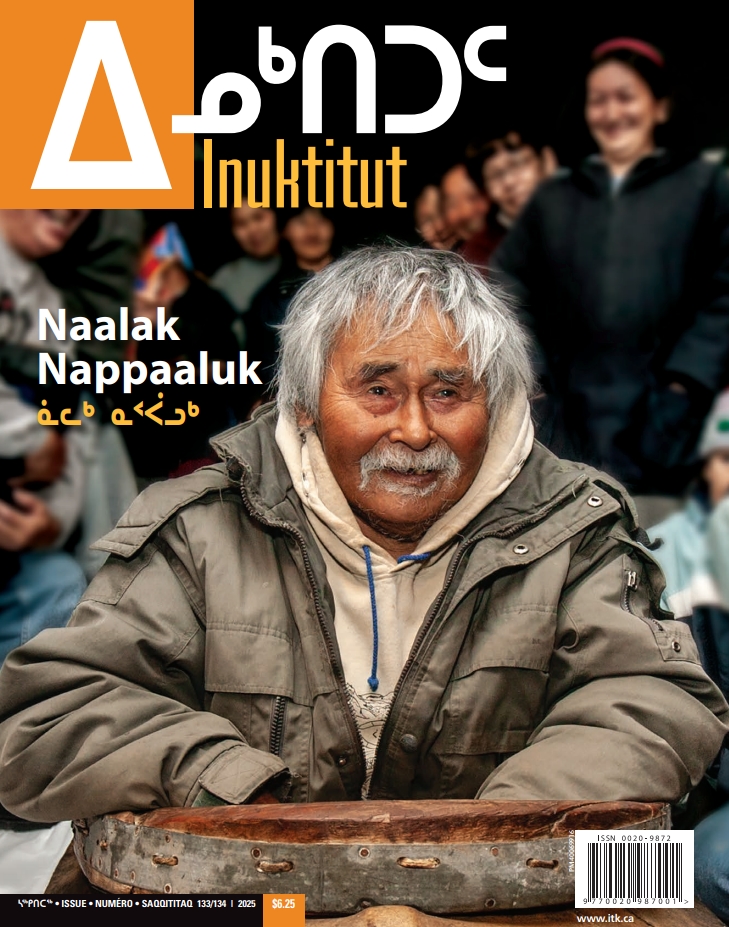

This past summer, a ship left a Vancouver shipyard and headed south for the Panama Canal. It will soon arrive at its home port of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, where it will be officially christened Canadian Coast Guard Ship Naalak Nappaaluk. This is the first of the Coast Guard’s Offshore Oceanographic Science Vessels and the first federal ship ever to be named after an Inuk.

This new vessel will be a floating laboratory for scientific research so Canadians can better understand our oceans, sea beds and climate change. Designing and building the ship was one thing — naming was another. As part of its reconciliation mandate, the Canadian Coast Guard is updating its vessel naming policy to incorporate more guidance from Inuit, First Nations and Métis peoples. They recently christened the CCGS Jean Goodwill, for example, after Saskatchewan’s first Indigenous nursing graduate. Naalak Nappaaluk was chosen for this ship in cooperation with Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Makivvik.

© Seaspan

Naming the new state-of-the-art science ship after Naalak Nappaaluk is a perfect tribute – before he died, the Nunavik Inuk was a leader, hunter, fisherman, midwife, storyteller, teacher and harvesting advocate. But he was also a consultant, astronomer, newsman, navigator and meteorologist.

“He was just my father,” says Qiallak Nappaaluk, mayor of Kangiqsujuaq. “Everybody has a father. But when he was gone, I realized my father was really knowledgeable because he had been teaching us many things. But the most important was home and family. Sometimes we face good things, happiness, sadness, but we have to work together.”

The Coast Guard said it was honoured to collaborate with Inuit leaders and formally recognize the contributions of Inuit elders. “The names of Canadian Coast Guard vessels are intended to honour and celebrate people and places of regional and national significance, representing the diverse cultures, peoples, and history in Canada,” said the Coast Guard’s Senior Director of Fleet Management, Ryan Tettamanti. “We know many Inuk elders are stewards of the land and seas, and we are thrilled to honour Mr. Nappaaluk’s legacy through our commitment to building a stronger understanding of Canada’s marine environment.”

The Coast Guard is “deeply committed to its reconciliation journey,” said Nicole Elmy, the Coast Guard’s Executive Director of Indigenous Relations, but putting an Indigenous name on a ship is just one part of it. “Of equal importance is the process by which names are selected and the opportunity for our staff and the public to learn about their significance,” she said. “We understand the power that names hold, that they can celebrate or be hurtful, and so we are approaching the naming of some of the new ships as an important, collaborative opportunity to work together with Indigenous peoples.”

Naalak understood the power of names. He proudly carried the names of his father and grandfather. He was a revered knowledge keeper who was passionate about preserving family ties and Inuit knowledge. He resolved to teach others and ensure the specific language of harvesting, travelling and surviving was retained and passed on. He was a consultant for multi-media Inuit communications company Taqramiut Nipingat Incorporated, the Avataq Institute (Nunavik’s cultural preservation organization), Nunavik teacher training programs, and other organizations, generously sharing his knowledge with anyone willing to listen.

When hunters began to advocate for the return of the bowhead whale hunt to Nunavik, Naalak was at the forefront. Though bowhead hunting had been banned since before he was born in 1928, he’d been told by his mentors how it had been done and he spent years fighting to harvest a whale. When a bowhead harvesting license was finally granted in 2008, a gray-haired Naalak joined the celebration at Akulivik Bay to greet the hunters as they returned and to enjoy bowhead maktaaq for the first time. He died two years later.

“It was something for Nunavimmiut,” says Qiallak, who was also on the beach when the whale hunters returned. “We ate it, and it seemed like we’d eaten it before, like we were used to it. I think it was in our blood. We were so excited. I remember it was a really good taste.”

Knowing how to hunt bowhead whales without ever having done it is extraordinary. But that was only one example of Naalak’s skill, capacity and contribution to society, Qiallak says

A gray-haired Naalak greeting the successful bowhead whale hunters at Akulivik Bay.

Naalak Nappaaluk in Kangiqsujuaq in October 2004, six years before he died.

He used to say that a woman needed to hold on to her husband when she was in labour and many men did not like to do that so he would be that person, coaching women through the birth and helping deliver babies, Qiallak says. He knew the Inuktitut names for specific stars — like Ullautut, Sakiatsiat, Tuktujuk — and knew that to navigate by the stars, you had to understand how they moved, over time, in the sky. He knew that a west wind created rough waves in the snow and that you could maintain your direction by closely monitoring the wave patterns. He knew how to protect himself if a polar bear charged. He knew ajaaja songs. He loved to sing them.

He learned most of these things from Alaku, the elder who raised him. Naalak was named after his father, Naalaktuujaq, and his grandfather Nappaaluk. But Naalaktuujaq died before Naalak was born and Alaku, a generous provider and elder, adopted the boy and mentored him.

Jobby Arnaituq, Naalak Nappaaluk’s nephew, addresses the crowds gathered to celebrate the launch the new CCGS Naalak Nappaaluk ship in Vancouver on August 17, 2024. © Seaspan

When he came of age, Naalak married a woman named Mitiarjuk. Mitiarjuk also became a renowned elder, educator, sculptor, and author. She is famous for writing Sanaaq, one of the first Inuktitut novels, and for helping to write one of the first Inuktitut dictionaries. Mitiarjuk passed away in 2007. She and Naalak had five children. They also raised two adopted children and two grandchildren and were godparents to dozens of others.

It’s important for Qiallak to mention all these relations because for her father, family was the most important thing. He and Mitiarjuk cared deeply for each other, she says, and kept each other alive.

Qiallak Nappaaluk helps to christen the Canadian Coast Guard’s newest science vessel named after her father, Naalak Nappaaluk. © Seaspan

“He used to say your family is really important. You have to know who your family is so you can be comfortable and help each other,” Qiallak said. “That was how families used to be. You had to know who all your relatives were so you could take care of each other. So, when you were in another community, it would still feel like home. And he made his home the same way for others.”

Many Nunavimmiut have been named after Naalak Nappaaluk and so when the new ship is christened, they too will see their name on the side. It is one more gift from Naalak to his family.

The family of Kangiqsujuaq elder Naalak Nappaaluk gather in Vancouver August 17, 2024, to celebrate the christening of the new ship, named after Nappaaluk. From left: Nappaaluk’s nephew Jobby Arnaituq, daughter Qiallak Nappaaluk and son Lucasi Nappaaluk. © Seaspan