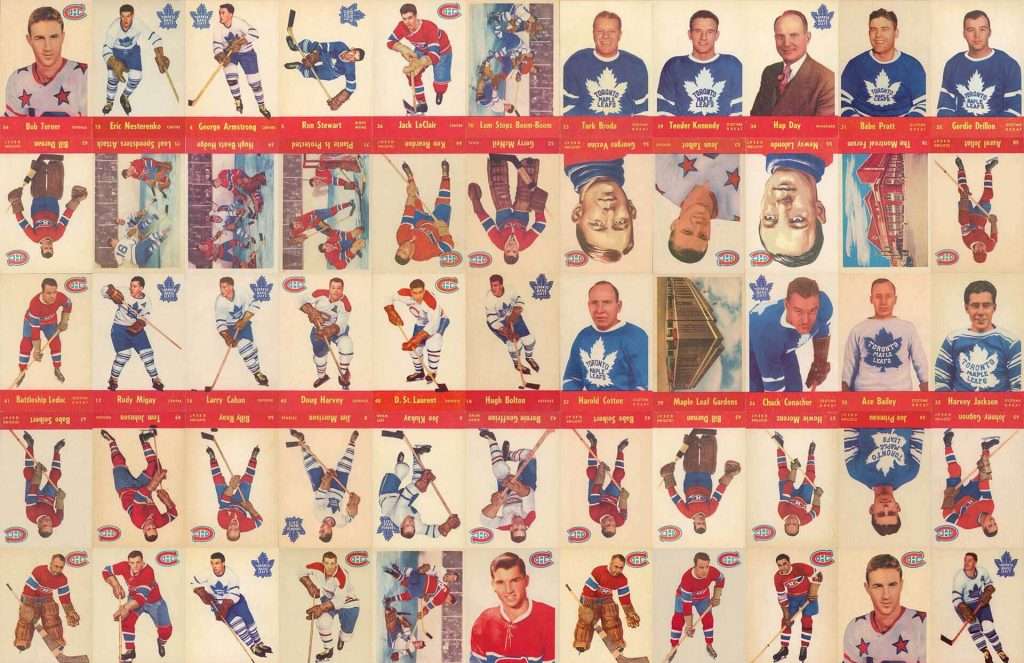

The Child and Youth Mental Health Team work out of this play therapy space in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, NL, and bring mobile play therapy to communities in Nunatsiavut.

The Healing Power of Play

YOU ARE SIX years old, and you’re greeted by a stranger who says they’re your therapist.

“Welcome to the playroom, you can do just about anything in here, and if there is anything you can’t do, I will let you know,” says the stranger.

You enter a room filled with toys, stickers on the wall, and a table with what looks like a sandbox, alongside some toys. You feel shy and nervous as you look around the room. The therapist has a smile on their face, and they sit down on the floor as you look to see what you want to try first.

“You can choose whatever you like,” the therapist says, as you eye a box of squishy beads in water on the shelf.

You pick up the box, open it up, and squish your fingers right through the beads. They feel bumpy and slimy. You then see mini figurines and you ask if you could put some in there with the squishy beads.

“You’re wondering if you can put them in there?” asks the therapist.

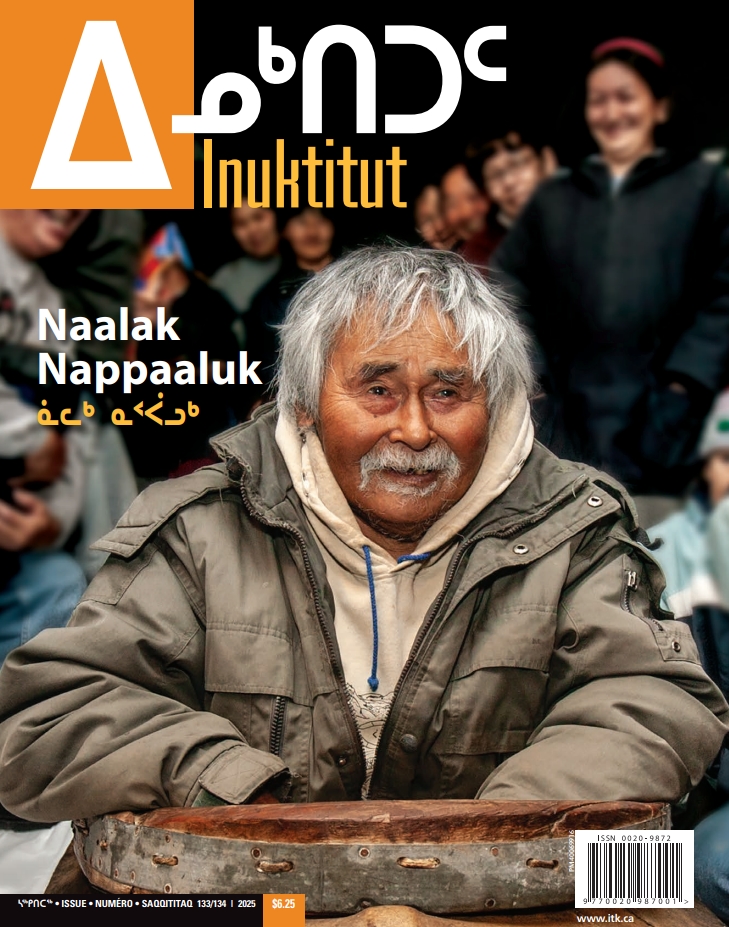

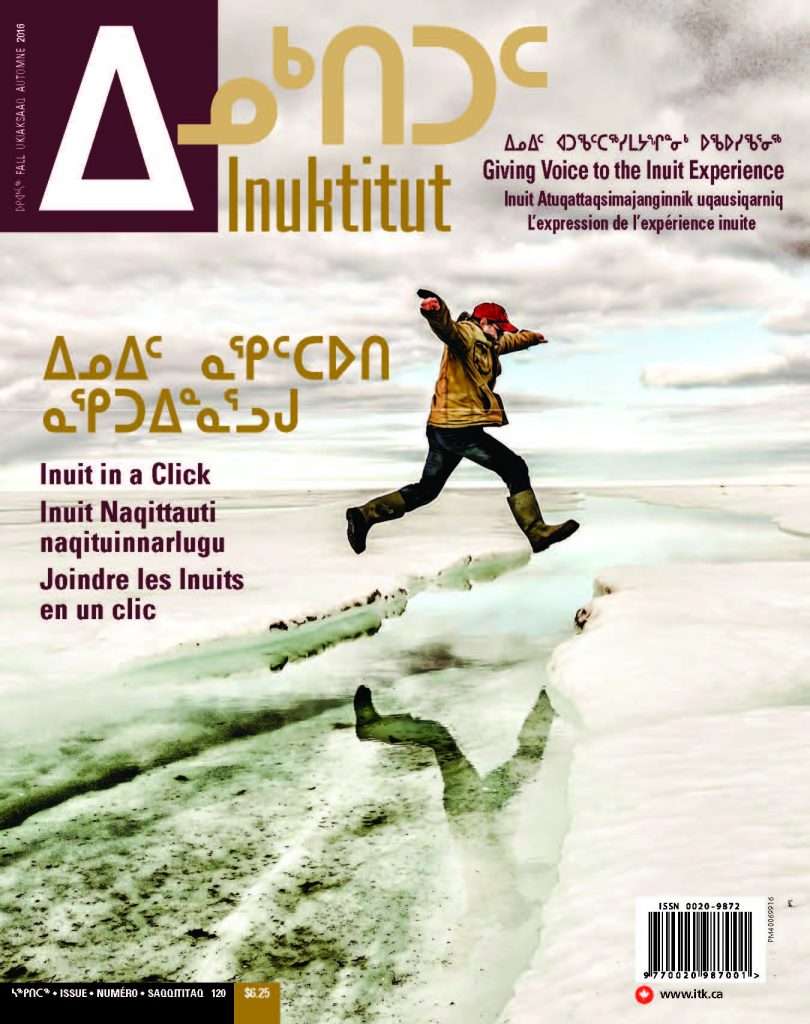

Jessica Lyall with her daughter Ada Lyall-Fewer.

You think to yourself that you probably wouldn’t be able to do this at school, or at home. You throw the mini figures in and watch as they all become slimy. You feel a little silly, but also content.

You see the sand tray and you quickly become interested in it. The therapist doesn’t seem bothered by you switching activities and, in fact, they seem interested in what you get to decide. They let you know that you can create a world in the tray, and sometimes they may ask questions about that world. This is all new, but it feels like you can do almost anything you want in here. You feel safe. You don’t feel as shy, and you want to come back and play more. A lot has happened to you, but you feel safe in here.

We are registered social workers Jessica Lyall and Grant Gear, and this is what a play therapy session may look like through the Nunatsiavut Government’s Child and Youth Mental Health Team (CYMHT), which was established in 2020 to provide Inuit-specific mental health services. As therapists, we often see children who are nervous when they come into the play therapy space in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the mobile play therapy spaces within the Nunatsiavut region. Play therapy, is a psychotherapy approach that uses play as a way of expressing or communicating one’s feelings It offers time to get to know the child on their time, and at their level.

We have seen families benefit from play therapy, and our team is continuing to experience growth. CYMHT provides virtual and in-person mental health services and support to the five Labrador Inuit communities (Nain, Hopedale, Postville, Rigolet, Makkovik). Support is also available in the Upper Lake Melville area (Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Mud Lake, and North West River).

Play therapy creates the opportunity for a child to play out their feelings and problems just as they are, and allows them to externalize events and emotions, while also exploring and making meaning of their experiences.

Through play, a child can share their stories and learned experience with the therapist. The therapist can then connect with the child’s own sharing and exploration of culture, tradition, and story telling. For children who have been through trauma, play can make it easier to recount, revisit, and remember painful experiences. Through the safety of play, a child can tell and understand their own story.

Therapist Jessical Lyall’s four-year-old daughter Ada Lyall-Fewer enjoys a sensory sand box at the Nunatsiavut Government’s Child and Youth Mental Health Team Play Therapy Space in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, NL.

Virgina M. Axline, an American psychologist and pioneer of play therapy, defined play as the “child’s natural medium of self-expression.” Because of its innate value, play is considered a child’s right, and one that is recognized and acknowledged by the United Nations through its United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. The convention calls for states to assure a child “the right to express views freely in all matter affecting the child,” the “freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art” and for a child’s education to encourage “development of the child’s personality, talents, and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential.”

The therapeutic powers of play may assist a child or youth and family with their healing. The strength of play is that during its practice, you are also building connection and reconnection. Within play, children and families often revisit moments or a person that hold a special place. As Inuit social workers, we appreciate that play therapy is easily adaptable to support Inuit culture, and it offers a time for revitalizing culture through play opportunities. Inuit are innovative and creative. Inuit continue to live off the land and share our teachings with one another, and that is a form of play.

Jessica Lyall, left, and Grant Gear, are registered social workers with the Nunatsiavut Government’s Child and Youth Mental Health Team.