Illustrations by Alexander Angnaluak

THE ATLANTIC OCEAN BORDERS the Labrador coastline from the northern end of the Big Land, where it meets Davis Strait to the southern end, which runs into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Storms have shaped the landscape as well as the People living on the coast. Conditions all along the coastline are harsh, but the northern climes are the hardest areas for people to adapt to.

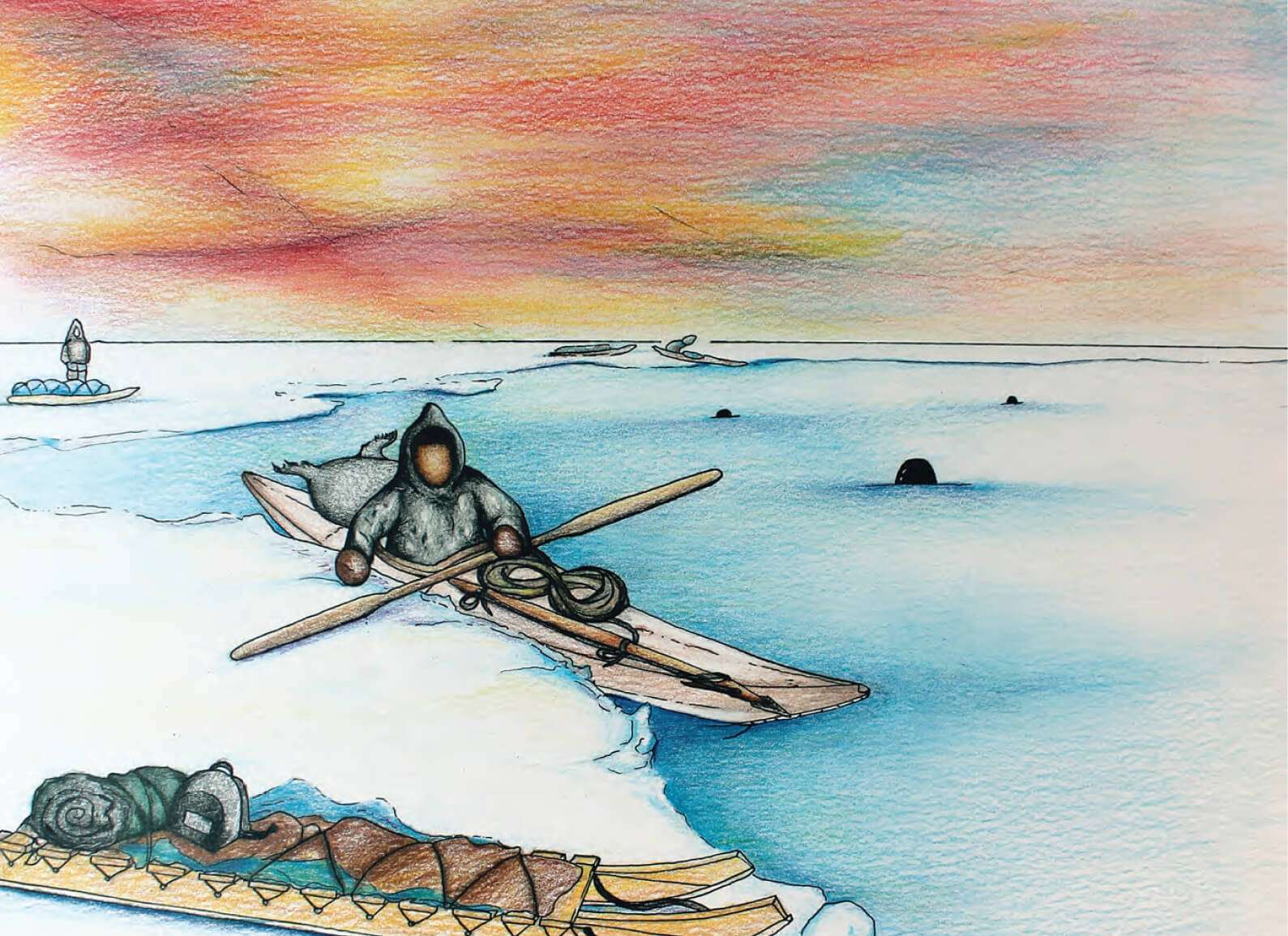

It was late April and a nor’easter had been roaring in from the Atlantic for a week. As the weather had been too bad for hunting, the Inuit living in Hebron were running short of food. Late in the evening of the eighth day, the storm blew itself out and an eerie silence filled the land. People emerged from their igloos to look at the sky to determine the weather for the next day. Hunting seals at the sinaa (floe edge) was uppermost in the hunters’ minds, but they knew theywould have to wait at least two days before venturing out onto the sea ice to shoot and dart those plump jar seals. Some hunters would haul their qajaqs on omemade qamutiiks (sleds) while others would just use harpoons and throwing hooks to snag the floating seals.

Jacko, his son Amandus and nephew Abia were among the eager hunters who left the village before daylight with eight sled dogs hurry ing eastward looking for seals to dart as they swam by the floe edge.

The day went by very quickly with the men having killed 12 plump seals while enjoying their day sharing steaming raw seal liver washed down with sweet tea boiled on the primus stove. They could see other hunters to the north and south, and when evening neared they got ready to return home because all the other hunters had already left the sinaa.

When Amandus went to get the team he climbed some piled up ice pans to scan the ice surface and his blood ran cold with what he saw.

In the morning they had run across a large crack in the ice surface that was covered with about three feet of hard-packed snow. The storm had broken up the ice and the strong current forced it to separate during the day. There was about 20 feet of open water between the ice floe and the land-fast ice to the west. They were stranded without a soul in sight and their qajaqs left ashore. This was a serious situation.

Illustrations by Alexander Angnaluak

IN EARLY JUNE THE ICE had moved off the coastline and people from the little settlements all along the Labrador coast were making their way to their summer fishing stations. My ancient uncle Julius sat atop the high hill behind his sod-covered summer fishing place smoking his pipe and looking out across the water at two large islands he knew to be 10 miles from land. The family had just arrived that day to get things ready for their busy fishing time and my uncle had walked over the land looking around and centering himself in the familiar environment that he loved. As he sat on the hill he thought he saw smoke rising from those far away islands but he knew no one would be out there yet: too early for fishing time.

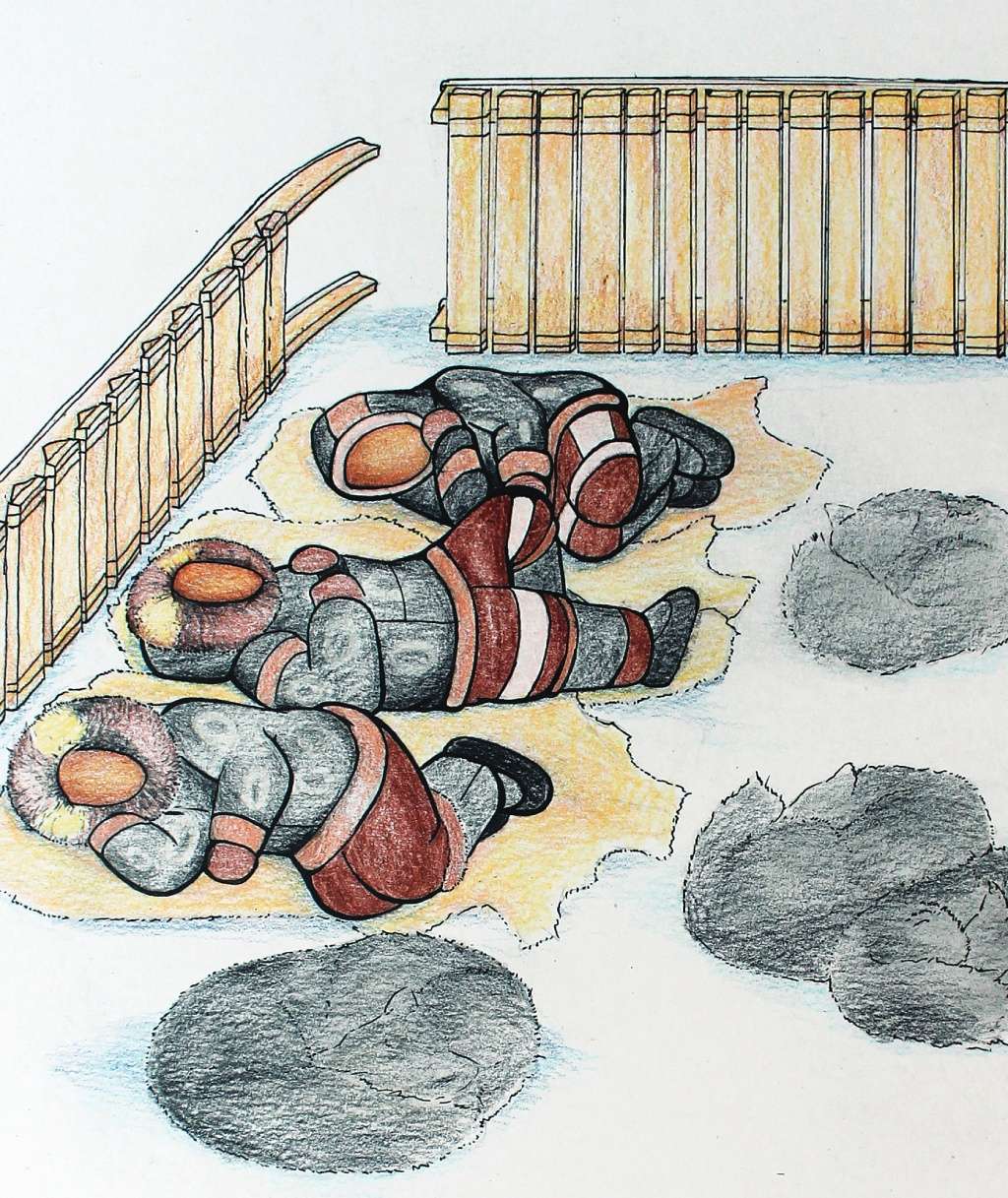

A week later some transient Newfoundland fishermen steamed into my uncle’s cove in a large fishing schooner. He told them about the smoke on the islands so they made ready to go out to see who may have made the signal. Two days later, they came back into the cove with three Inuit hunters grinning from ear-to-ear. They had survived two weeks on a large ice pan, drifting south approximately 250 miles with the Labrador current, nearly drowning and getting smashed to bits on the cliffs of Cape Kidlaipit, and finally going aground on the island that saved their lives.

They were very hardy men sleeping without cover in their sealskin clothing in all manner or weather and living off seal meat while keeping their dogs alive and facing each difficulty with stoic determination.

THESE MEN POSSESSED great humility and never boasted about their exploits, simply telling snippets of their adventure and leaving the rest to the imagination of the listener. It is the Inuit way, to endure trials with humility and to prosper from adversity while also serving as living proof that adaptability is one of the amazing wonders of survival.

At the end of their adventure, the men from Hebron returned to their families: no fuss, no bragging, just the humbleness that kept them alive through what must have been nothing but a nightmare. Northern men have a spiritual connection to the land and all its elements, both visible and invisible. They seem to possess some sort of inner strength that sets them apart from others. Sometimes I have stood next to a northern man out on the land and felt his inner strength, I have watched as he sat on the side of a high mountain and became one with his surroundings. There remains in us something intangible and not fully understood but keenly felt, something that binds us to our past and connects us with our half-forgotten roots. It is the spirit of the ancestors that keeps us alive and vibrant; our ties to the land and animals are so strong they will never be replaced in our ancient hearts by modern conveniences.

Illustrations by Alexander Angnaluak

Illustrations by Alexander Angnaluak