David Serkoak stands outside Parliament in Ottawa. Barry Pottle

An interview with David Serkoak

The Ahiarmiut were relocated over and over again. In 1949 the Government of Canada bulldozed their camp at Ennadai Lake, southwest Nunavut, and began a devastating decade-long relocation process. David Serkoak lived through the relocations as a child. The retired teacher and principal in Nunavut now lives in Ottawa. Last January, in Arviat, the 21 remaining Ahiarmiut relocation survivors finally heard the Canadian government apologize.

The photos accompanying this interview were taken in 1955 at Ennadai Lake by photographer Fritz Goro, while on assignment for Time magazine. They are published with the permission of the Smithsonian Institution’s Arctic Studies Center, and the Goreau family.

Inuktitut magazine: First, tell me about Ennadai Lake.

David Serkoak: Our camp, Iqalliarvitnaaq, was maybe two kilometres away from the village, a little fishing place. That’s where I remember having our tent and igloos. Our parents and grandparents relied on the wildlife: freshwater fish, trapping, the migration of caribou.

IM: Can you explain who the Ahiarmiut are?

DS: A group, totally reliant on caribou and freshwater fish for livelihood; Ahiarmiut means “the people from the mainland.” Scholars, researchers and authors sometimes labelled us the “people from beyond,” “out of the way dwellers,” or put us as part of the Caribou Inuit. Many of my fellow Inuit consider my group the lowest of the low in Inuit society. And that was really in my head for a long time. They didn’t think highly of us because they thought we were poor from an ‘uncivilized world’ setting, moving into a ‘civilized world’; the primitive Eskimos. Even today, that feeling is still there.

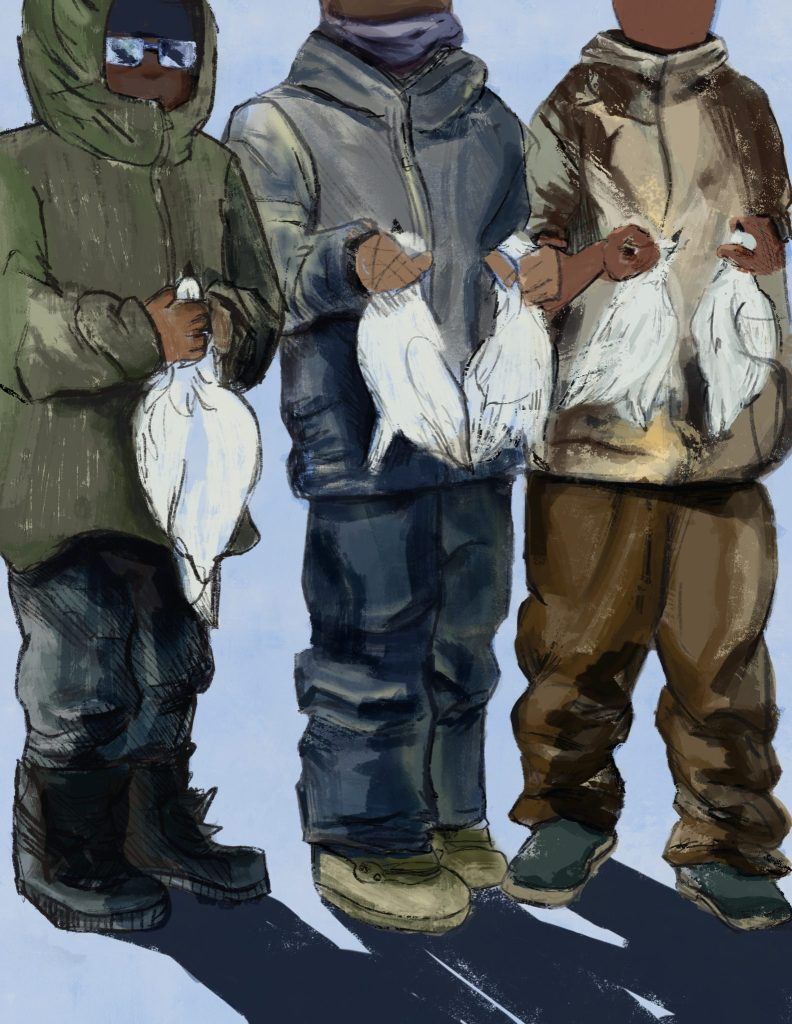

IM: Looking at these historic photos, what comes to mind?

DS: Many times when the government reported back from their trips to Ennadai Lake to see us, they would say that we’re not in good condition. But looking at the photos, they look very healthy, physically. Their clothing looks very worn out. That’s not an issue. The issue is how healthy they were without outside interference. And they thrived.

“This would be like the father of all the drums,” says David Serkoak. The drum maker is using the shoulder blade of the caribou to scrape hair off the caribou skin.

IM: Can you paint a picture of daily life at the camp?

DS: Everyone worked together. They built their own transportation, making kayaks. Women would help to cover it with sewing. Women were drying caribou meat in the fall, picking aqpik berries and putting it away for later use. The men cut up meat in the fall and buried it with rocks — caching the meat. They would either walk back or use the dog team in the middle of January when they needed it and dig it up. Some Elders and hunters still use that method today.

IM: Do you remember the relocations?

DS: They first moved the family to Nueltin Lake in 1949. I wasn’t even born yet. There was never a consultation about if we wanted to move. It was quick, according to the Elders. There were no supplies attached to the move, no services, no survival equipment. Three people came to the tents and ordered everyone out and bulldozed all their belongings with heavy equipment. Just like that. They flew us to Nueltin Lake. It was a short stay, my Elders told me; four people died. The following fall, they all walked back to Ennadai Lake, three months of walking. They were back in Ennadai Lake by mid-winter.

David Serkoak’s father, Miki, and Owlijoot shedding hair from caribou.

IM: What was the supposed reason for the first relocation?

DS: One is that we were getting in the way of the personnel at the radio station, getting too dependent. Another justification was there was commercial fishing at Nueltin Lake by First Nations people, and trading.

IM: Were you born in Ennadai Lake?

DS: Yes, I was born shortly after the walk back from Nueltin. Years later, in 1957, a decision was made to move us again to North Henik Lake, which sits between Ennadai Lake and now-Arviat. When we landed at North Henik Lake, I remember brand new tents were up already with a little box of food rations. It was a one-way ticket of no return. We couldn’t walk back. The most tragic thing during that short stay is when the food ran out.

IM: What did the group do to survive?

DS: If you were healthy, the closest place to get supplies is three days’ walk, one way, to Padlei, [a Hudson’s Bay trading post]. Some people died of starvation, a few by exposure, a couple people by murder. One day three guys came across a cabin belonging to a mining expedition. They broke the lock and took food to feed their families. Not long afterwards, authorities came and arrested them, and took them to Eskimo Point to do hard labour, leaving their families; that made it more difficult for the group. With all this happening, we had to move to Padlei, a three-day walk. Every family made their own way. And after a short stay, authorities came and looked for people that had died of old age or starvation, abandonment, or by the murders. Then, all the Ahiarmiut were airlifted to Eskimo Point in 1957. I was about six years old.

IM: Why Eskimo Point?

DS: The RCMP were doing investigations because of the murders. Nobody was allowed to mix with people from Eskimo Point. One lady was charged for murder and also for abandoning children. She was tried in Rankin Inlet and was found not guilty. After the trial, we were told we’d be heading north, this time by boat. They created a little Ennadai community for all the Ahiarmiut close to Rankin Inlet, called Itivia. We didn’t stay long. We had just started kindergarten but were moved again by boat to Whale Cove, and it was back to square one. It was all tundra, this time no trees. It was hard to be back to iglu living. There were a few Ahiarmiut from Back River and Baker Lake who were flown in at the same time. We all ended up in Whale Cove together in 1960.

IM: How did the group cope with these constant relocations?

DS: I think the stress was more on our parents. We were children, we were just put on the back of our mothers. In Whale Cove, our parents really had to make a fast adjustment. The parents had to relearn some of their livelihood living on the coast. They weren’t accustomed to the tides and had never seena sea mammal. Most of us didn’t get into the habit of eating sea mammals.

IM: Decades later you created the Ahiarmiut Relocation Society. What

prompted you?

DS: It was 1998. I always had an interest in why we were moved. It never goes away. Leading up to 1999, I was hired to work at the new Nunavut Education headquarters briefly. Part of the job was to go to communities. One trip was to Arviat with the Deputy Minister. I stayed behind and organized all the Ahiarmiut to have the first meeting with the Elders. They talked to us for seven hours. That night, the younger generation got together and decided to create a group. The Elders told us all these horrible stories. People needed to know.

IM: That was a while ago, what happened between then and the apology this year.

Left to right: David Serkoak’s late mother Qahuq, and Nutaraaluk.

Alikashuak beside a skin tent.

DS: If you were healthy, the closest place to get supplies is three days’ walk, one way, to Padlei, [a Hudson’s Bay trading post]. Some people died of starvation, a few by exposure, a couple people by murder. One day three guys came across a cabin belonging to a mining expedition. They broke the lock and took food to feed their families. Not long afterwards, authorities came and arrested them, and took them to Eskimo Point to do hard labour, leaving their families; that made it more difficult for the group. With all this happening, we had to move to Padlei, a three-day walk. Every family made their own way. And after a short stay, authorities came and looked for people that had died of old age or starvation, abandonment, or by the murders. Then, all the Ahiarmiut were airlifted to Eskimo Point in 1957. I was about six years old.

IM: Why Eskimo Point?

DS: The RCMP were doing investigations because of the murders. Nobody was allowed to mix with people from Eskimo Point. One lady was charged for murder and also for abandoning children. She was tried in Rankin Inlet and was found not guilty. After the trial, we were told we’d be heading north, this time by boat. They created a little Ennadai community for all the Ahiarmiut close to Rankin Inlet, called Itivia. We didn’t stay long. We had just started kindergarten but were moved again by boat to Whale Cove, and it was back to square one. It was all tundra, this time no trees. It was hard to be back to iglu living. There were a few Ahiarmiut from Back River and Baker Lake who were flown in at the same time. We all ended up in Whale Cove together in 1960.

Anowtalik and Aajaaq Mary Anowtalik