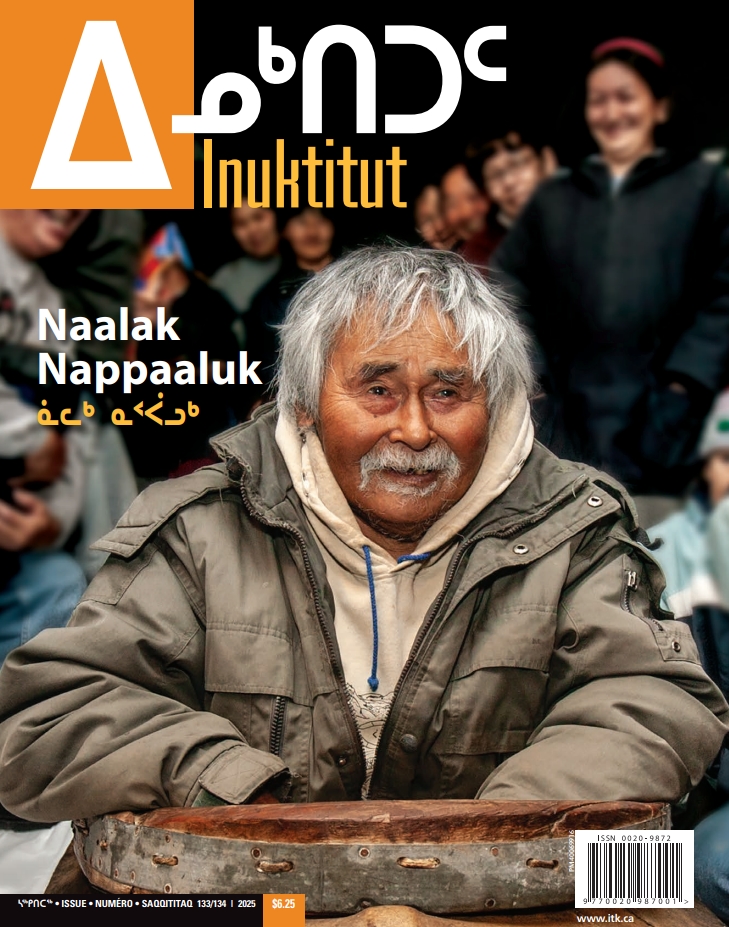

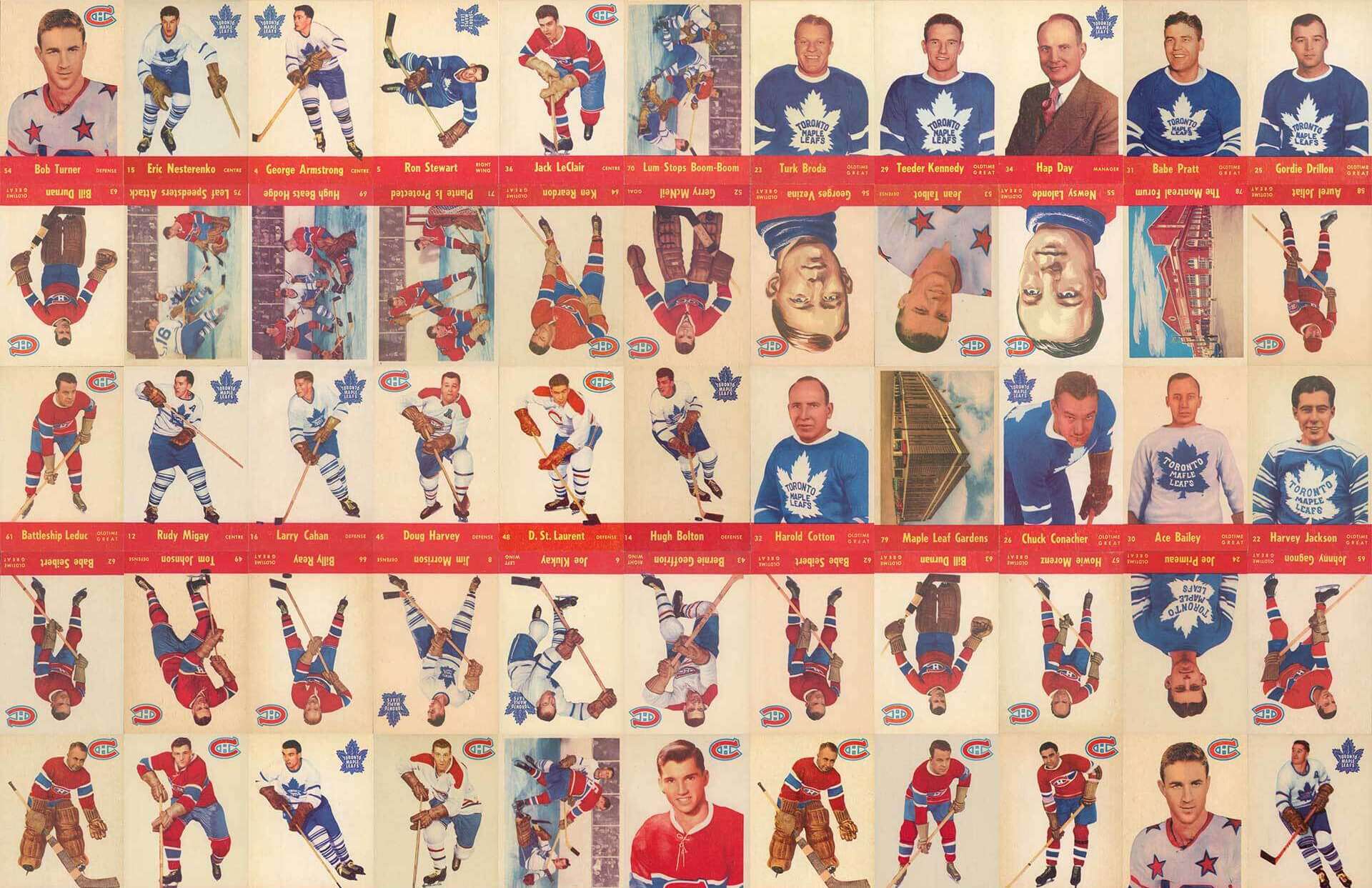

President Natan Obed spent time during the pandemic recreating this sheet of hockey cards from 1955. Courtesy of Natan Obed

Natan Obed on Hockey Cards and Pandemic Puzzles

I IN 2020, when the COVID‐19 pandemic shut everything down, Natan Obed, President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, like many people, went searching for a distraction. What he chose would take him 18 months to complete and solve a 70‐year‐old mystery connected to his favourite set of hockey cards from 1955. Obed has been collecting hockey cards since his uncle Andy bought him his first packs when he was a child in Nain, Nunatsiavut. He’d lose himself in those uniformed faces, sorting and re‐sorting them according to statistics and scenarios. He probably owns about 100,000 cards today and still finds joy when he pulls them out.

The hobby grew from his love of hockey, of course. Obed was on skates by age two and his middle childhood in North West River, Labrador, was defined by sweat and frostbite: firing a frozen puck against the boards of an outdoor rink for hours and deking out imaginary opponents in NHL daydreams. He developed a powerful slapshot, advanced into competitive leagues, and ended up playing Junior A in the United States as a young man.

A face-off with Uncle Andy when Natan Obed was three years-old. It was Andy who bought Obed his first hockey cards. Courtesy of Natan Obed

Obed recalls a moment in 1996 when he was 20 and playing for the Helena Ice Pirates in Montana. It was Game 7 against the number one team and the underdog Pirates had rallied after losing the first three games in the playoff series. Obed, on defence, unleashed a low wrist shot from the point, the goalie popped out a rebound and Obed’s teammate scored to win in overtime.

“That was the most exciting moment that I’d ever been a part of in hockey,” says Obed. “The whole community was behind us and we were playing in sold‐out stadiums. There was a feeling of excitement from that experience that is unforgettable.”

His commitment to a better future for Inuit, his trust in teamwork and consensus, the grit to keep fighting an endless battle for national respect, equity and self-determination for Inuit, and the belief that goals and hard work matter —they all have roots in hockey.

As someone who has spent most of his adult life working to advance Inuit rights and priorities, it makes sense that Obed’s favourite hockey moment involves an assist. Obed is more than halfway through his third term as President of ITK. He’s a passionate advocate for Inuit rights, a soft‐spoken public policy guy and an eloquent public speaker. But that passion looks different on skates.

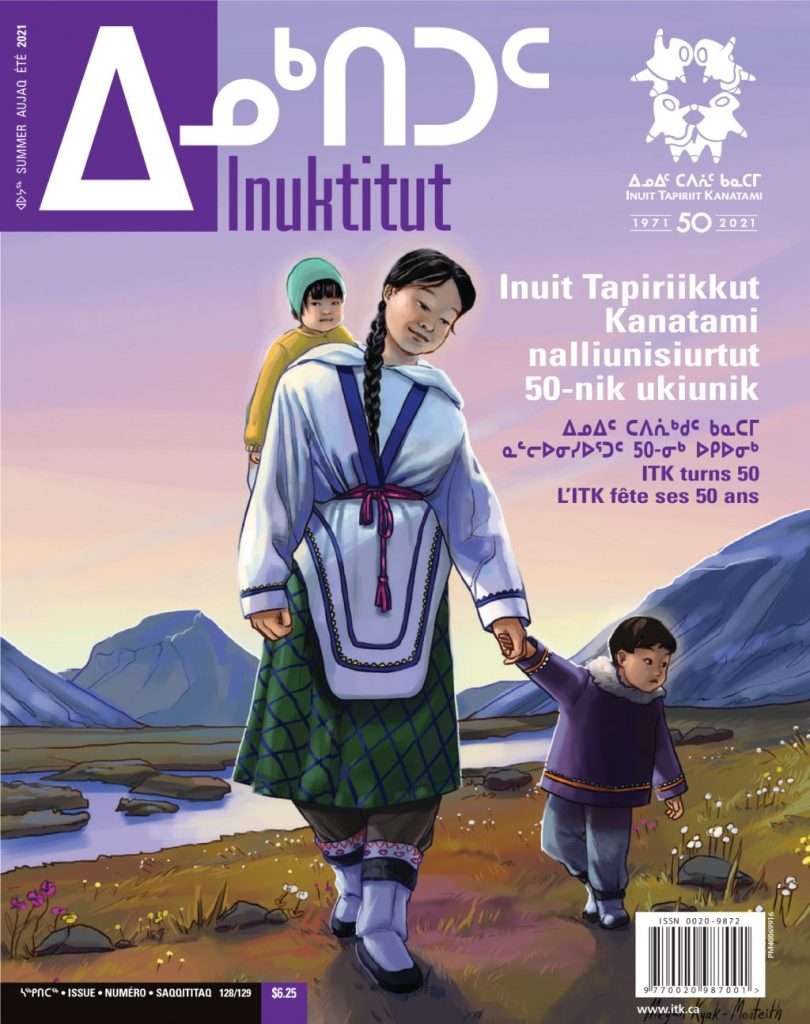

© ITK

“Yeah, I’ve been thrown out of games,” he says. “I’ve definitely done things I wouldn’t do today.” He didn’t get mad when he fought on ice, and he never purposefully tried to hurt anyone. “But there’s a tribalism in hockey. You’re defending your teammates. I played Junior hockey in a time when fighting was very common.”

Obed has been collecting hockey cards since his uncle Andy bought him his first sets when he was a child in Nain, Nunatsiavut.

When Obed says he “owes hockey a lot,” he’s not just talking about how the sport allowed an introvert like him to make friends and feel connected.

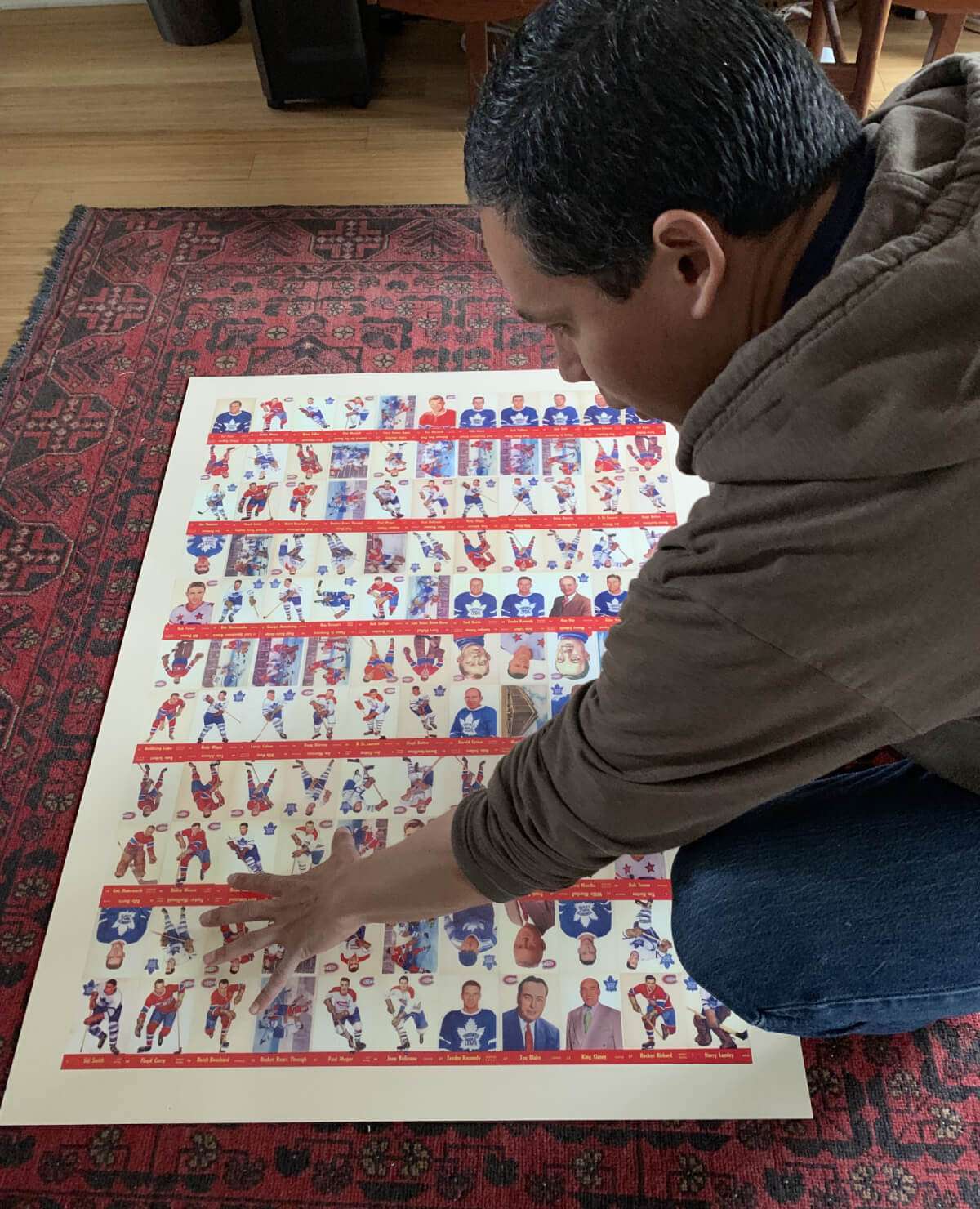

ITK President Natan Obed pieced together this lost sheet of hockey cards from 1955. © Patricia D’Souza

His commitment to a better future for Inuit, his trust in teamwork and consensus, the grit to keep fighting an endless battle for national respect, equity and self‐determination for Inuit, and the belief that goals and hard work matter—they all have roots in hockey.

And so it’s natural that he’d periodically be drawn back into hockey cards and the nostalgia they bring. During the pandemic, he’d have Zoom chats with fellow card hobbyists and sometimes they’d talk about a set of 1955 cards made by Parkhurst Products which featured the Montreal Canadiens, Obed’s favourite team, and the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Here’s where the mystery comes in.

Hockey cards start in a factory as uncut sheets—collectors’ items if you can find them—but as far as anyone knows, no sheets from that 1955 set survived. Because of that, no one knows what those sheets would have looked like. If you are not a card collector, you might think, so what? But if you’re a committed hobbyist and a skilled researcher with time on his hands, you might do what Obed did—get sucked into the mystery.

Luckily, there were many “mis‐cuts” in the set: cards that included slivers of adjacent cards because of imprecise cutting. It helped that Parkhurst printed the same set for Quaker Oats for cereal box prizes. Though the backs were different, the front of the sheet would have been identical and there are a lot of mis‐cuts in the Quaker set too.

Obed fell down the rabbit hole, examining mis‐cut cards he owned and those shared by friends and collectors. Which cards had duplicates on the sheet? Which were grouped together on the sheet and short‐printed to limit Quaker’s prize giveaway? As the pandemic wore on, the card project was a calming interruption in the face of uncertainty, fear and anxiety. Finally, late in 2021, he felt confident that the job was complete: he’d recreated something that hadn’t existed since 1955.

Between hockey hits and a series of demanding manual labour jobs, Obed, at age 20, ended up with a ruptured disc in his back. He underwent surgery and a long recovery during which he had to rethink his hockey dreams. He landed at Tufts University in Boston on a hockey scholarship because it offered a quality education and the tools to remake his future. “I was very aware at that time how special it was to be able to play hockey competitively until I was 25,” he says. “But also, it was over. It was incredibly sad. It had been a huge part of my identity.”

Obed still plays hockey twice a week on two different teams. He watched Jordin Tootoo pave the way for Inuit in the NHL and knows the future of professional hockey for men and women will include more Inuit. But he also knows that reaching a goal is secondary to what you find on the way there.

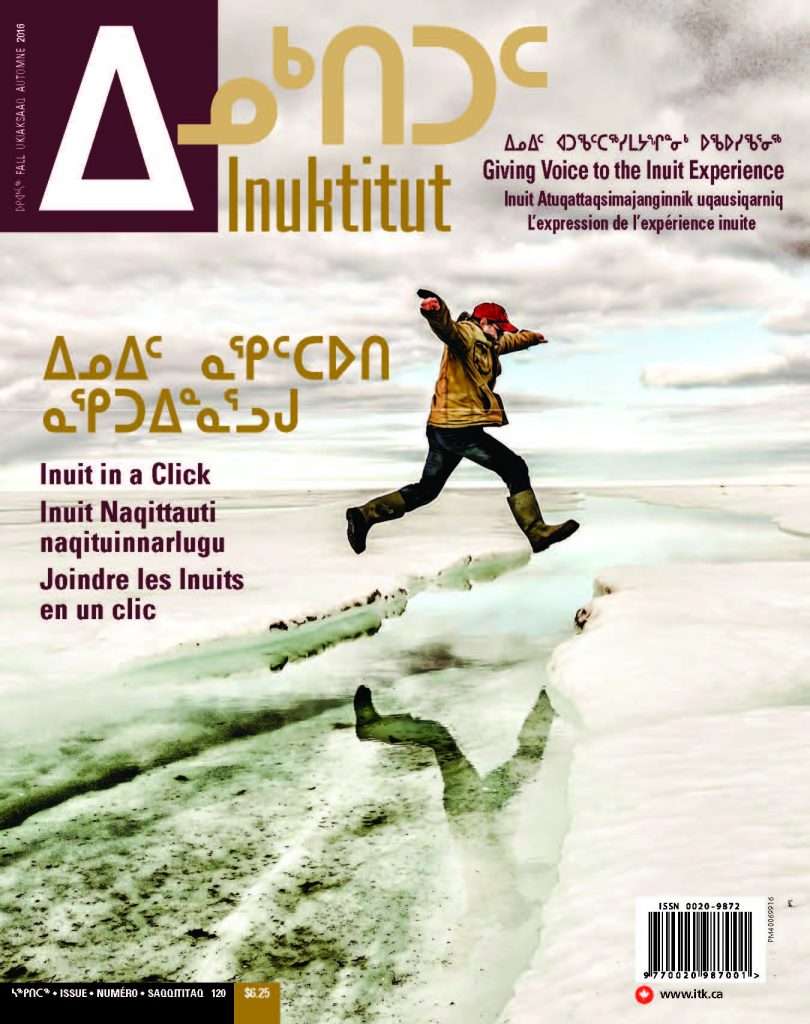

Obed was team captain for the 2024 Tea and Bannock Cup game between Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Métis National Council. © Robert Hoselton

“Hockey was a way for me to try to achieve a goal that I wanted to achieve, not something someone else set for me. But the pursuit of a goal sometimes is the most important part… it often leads to a maturity and self‐discovery that you may not otherwise get. And for me, it prepared me to have a successful career fighting for Inuit rights.”

As for that 1955 hockey card sheet, his designer friend laid it out to specs and Obed had the sheet printed on yellowed paper stock for effect. It’s possible that it might be worth something to a collector, but Obed didn’t do it for money. He loves hockey cards and the memories they hold—of cold outdoor rinks, of watching the Habs win the Cup and of his childhood dream of playing pro. He’s hoping this unusual labour of love brings joy to those who share his passion.

“That’s part of the fun of being a sleuth, you get to solve some of these questions that nobody has answers to. I mean, it’s just cool. It’s an interesting piece of collectability and its own little piece of art,” he says. “But I don’t think I’ll ever do a puzzle that difficult to solve again.