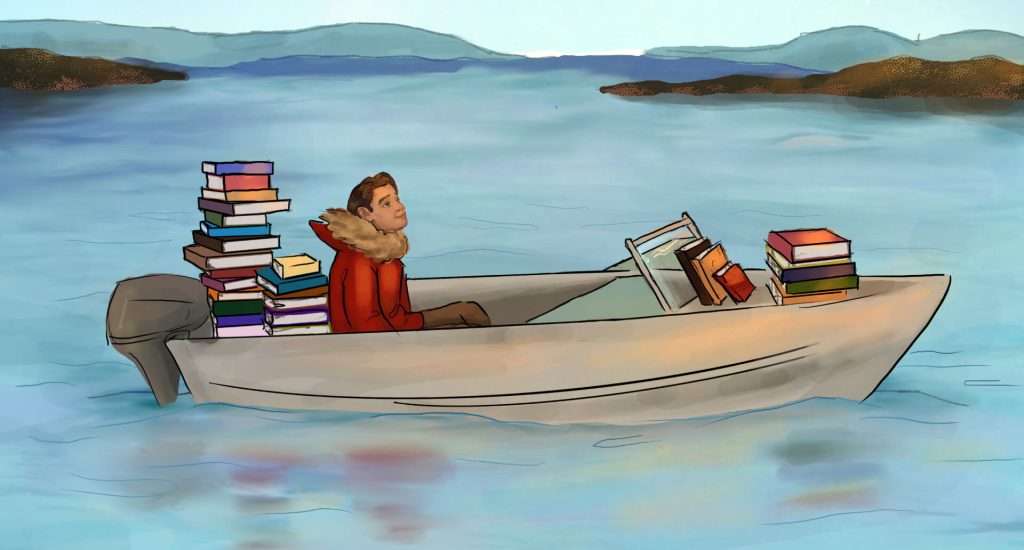

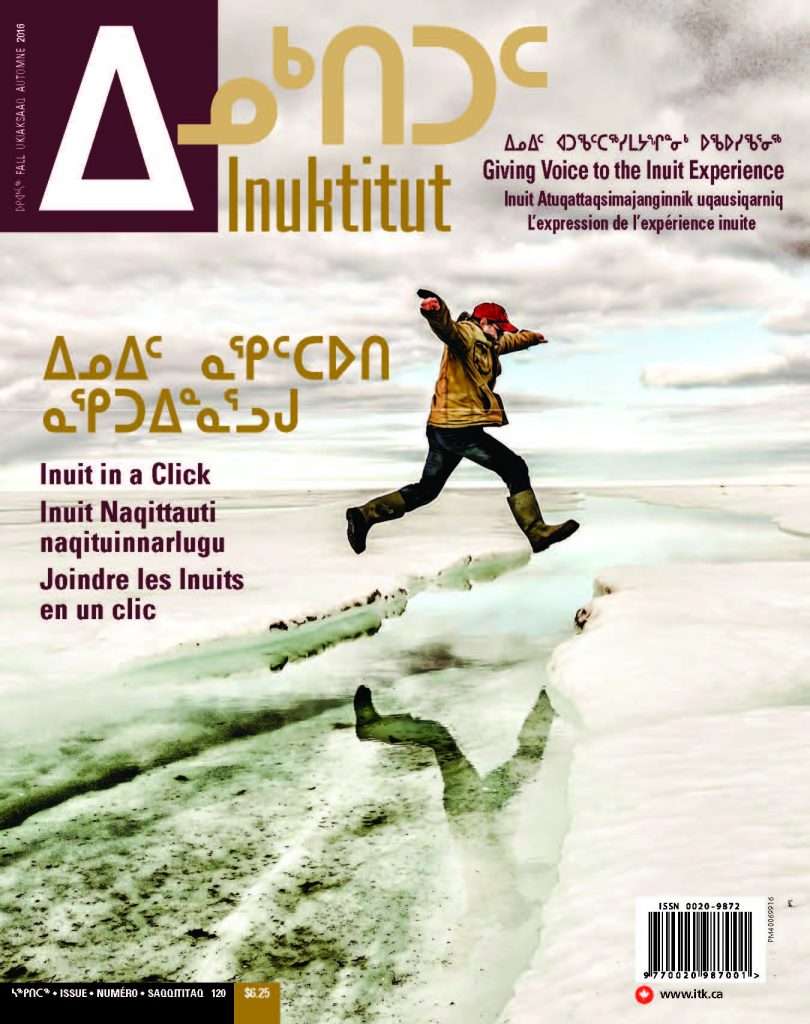

Mya Paul, her Great Auntie Molly Nogasak, and Launa Paul, August 2019, traveling to Uncle Charles’ summer camp by boat. © Myrna Pokiak

The North is My Bank

IN THE SUMMER OF 2019, I flew with my three daughters to my hometown of Tuktoyaktuk, from Yellowknife, to practice the sustainable, age‐old tradition of beluga harvesting. Watching my girls, aged 10, 8, and 1, participate in a harvest at the mouth of the Mackenzie River, where generations of our family have survived for centuries, was a highlight for me as a mother.

The North is my bank. They left it as our inheritance, to the future of Inuvialuit.

The beluga harvest is one of many Inuvialuit traditions passed down from our Inuvialuit forefathers, and it continues to teach lessons and build connections to our heritage.

Myrna’s daughter Launa Paul feels the soft skin of the beluga flipper harvested by Neil Kuptana the night before. © Richard N. Hourde

I was the curator of the exhibit “Qilalukkat! Belugas and Inuvialuit: Our Survival Together.” This exhibit is currently installed at the Museum of Nature in Ottawa, a re‐created exhibit that was first seen at the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife. The exhibit tells the story of one family’s connections to the land and sea, and the Inuvialuit cultural connections to the beluga whale. The photos, videos, and artifacts in the exhibit detail the importance of the harvest, and they’re specifically selected to represent various parts of this tradition. The exhibit preserves moments in time, life‐long memories, and hopefully it inspires Inuit to continue practicing our culture. This exhibit was made possible because of the countless Inuvialuit families that have ensured that our teachings have been passed on. I thank those who have monitored the whale population and respected our environment carrying forward the vision of our ancestors. As my grandfather once said, “The North is my bank. They left it as our inheritance, to the future of Inuvialuit.”

The beluga harvest is a necessity and not only for nutritional food. The tradition teaches respect, patience, and commitment. Respect is taught by observing and understanding whale swimming patterns,paying attention to the wake of the waves, and the smell of the ocean air. The weather teaches patience, as the wind and skies determine when we can hunt, day or night.

While out on the water last summer, windy conditions made tracking whales difficult. We waited patiently, floating with the motor off, watching for the blows of the whales. We followed the wake of waves, sitting in silence. This is what I love — no television, no Internet — simply embracing the place our Inuvialuit ancestors left for us.

I took my girls hunting because I wanted them to feel the pride that comes after the harpoon pierces the whale. I wanted them to learn as I had been taught — by family.

My auntie Molly Peter Nogasak, auntie Ida, uncle Charles Pokiak, and my cousin Verna’s son, Anthony Pokiak, were all by our side. I will be forever grateful for their knowledge.

Documenting these moments and displaying these photos alongside five generations of our Inuvialuit family practicing this tradition was important to me. This is what the harvest is about — carrying tradition and allowing relationships to blossom.

Charles Pokiak teaches his son James Pokiak how to cut the whale flipper to be preserved in whale oil (uksuk). © Myrna Pokiak