The Inuvialuit reindeer herd is growing each year. © Elizabeth Kolb, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

Food Security For Inuvialuit

IT WAS “A BIG STEP” FOR INUVIALUIT, says Brian Elanik, when—over the course of a week in September 2023—he and his team butchered the first 50 reindeer harvested from the regional herd. “That’s our herd that will supply the Inuvialuit Settlement Region with traditional meats and hides,” says Elanik, an operator at the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation’s Inuvik‐based Inuvialuit Country Food Processing Plant. “We brought them into the plant, hung them up, let the blood drain overnight. We made roasts, diced meat, ground meat, sausages, ribs. We try to utilize everything from the animal to provide for our people.”

I’ve dropped off Elders’ boxes and they’ve literally cried saying thank you because they don’t have family that hunt for them. They don’t get country food, and this is food that they’ve grown up with,” says Wade.

Operated out of two connected trailers, the plant is changing what food security looks like for households across the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR). Opened in the spring of 2021 as part of pandemic‐related efforts to decrease community reliance on southern food markets, the plant has seen over 60,000 pounds of country food delivered to Inuvialuit at no cost through semi‐annual food baskets to the region’s six communities of Inuvik, Aklavik, Sachs Harbour, Paulatuk, Ulukhaktok, and Tuktoyaktuk. While reindeer is a new menu item, food boxes also feature moose, muskox, beluga, rabbit, ptarmigan, geese, white fish and berries.

“The plant is addressing two issues that we’re having up here. Number one is food insecurity. We’re providing country food to people that may not have the means to go out and get country food,” says Brian Wade, director of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation’s Inuvialuit Community Economic Development Organization (ICEDO), which runs the plant.

The second concern the plant helps curb, Wade says, is the limited income earning opportunities in ISR communities.

Gilbert Thrasher. The IRC hopes to build a permanent plant in the future. © Elizabeth Kolb, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

“We’re creating an economy and providing a paycheck to harvesters. They can start bringing an income home with skills that they’ve obtained through their whole life, and mastered,” Wade says.

When it can, the plant also provides food for on‐the‐land programs, Elders luncheons, and to daycares and shelters.

This also creates an economy for women who go out and pick berries, and for little kids out ice fishing with their families. They’re able to sell their excess harvest back to this plant,” says Wade.

“I’ve dropped off Elders’ boxes and they’ve literally cried saying thank you because they don’t have family that hunt for them. They don’t get country food, and this is food that they’ve grown up with,” says Wade.

To source its product, ICEDO follows the harvest cycle of each community and relies on hunter and trapper groups to connect with harvesters throughout the region.

Patricia Rogers, resource manager for the Inuvik Hunters and Trappers Committee says on its own the organization wouldn’t have the funds to support the increase in paid harvesting the Inuvialuit County Food Processing Plant has created for Inuvik.

“We pay the harvesters, and then we invoice the plant,” says Rogers. “It’s helping our membership with extra funds and to get reimbursed for work they love to do. They’re not only getting reimbursed but they’re helping people who aren’t able to get country food.”

While country food is integral to Inuit culture and identity, as well as physical and mental health, harvesting on the land is expensive. It requires special equipment and fuel that many families throughout Inuit Nunangat can’t always afford.

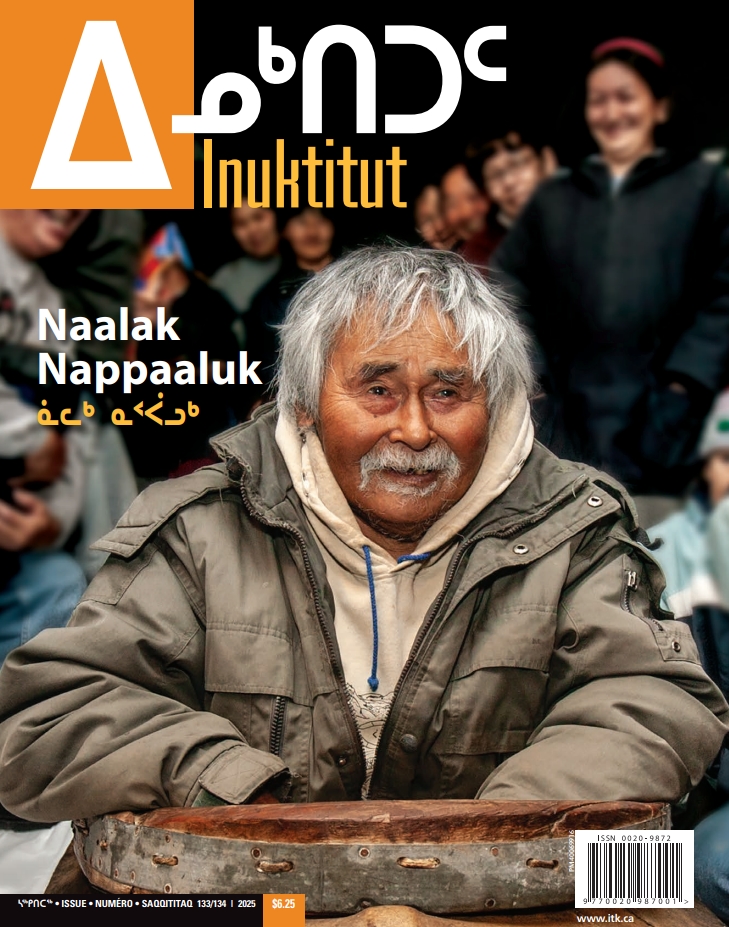

Brian Wade and Elder Paul Voudrach. Elders look forward to the food they grew up with. © Elizabeth Kolb, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

By definition, a person is food insecure if they do not have access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. For Inuit, this can mean they don’t have access to country foods.

In 2021, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami released an Inuit Nunangat Inuit Food Security Strategy. It describes food security among Inuit households as a public health crisis in Canada driven by poverty, cost of living, climate change, inadequate infrastructure, and systemic racism. ITK found that country food makes up for a quarter to half of all protein intake within Inuit Nunangat, and significantly contributes to an intake of iron, B and D vitamins. As well, 85 per cent of Inuit 15 years and older hunt, fish, or trap, and nearly half gather wild plants. Such data supports the idea that food security programming should foster regional food production, allow residents to make a living from local food systems, and invest in Inuit harvesting practices.

Elanik, who hails from Aklavik, grew up hunting, trapping and fishing for his own food. He says the plant makes breaking down large animals a lot more efficient. When staff work on large game, like moose, muskox, and reindeer, they might process up to 800 or 900 pounds of meat in a week, Elanik says.

ICEDO has freezers in every community for harvesters to store food while it waits to be shipped to the plant.

“It’s a long process from start to finish, just one muskox,” Elanik says. “That’s a lot of meat to be processed so we break it in quarters and work at it at a steady pace. We take the hind quarters, the front arms, break it down into pieces we know our people will enjoy.”

The plant opened shortly before the IRC gained full ownership of its Inuvialuit reindeer herd, in August 2021. Reindeer have been herded around the Mackenzie Delta since the mid 1930s, when the Canadian government brought the animals in from overseas to address a caribou shortage. Together, the herd and plant support a vision to bring local and protein‐rich foods to Inuvialuit households. As the reindeer herd continues to grow—there are roughly 6,000 now up from 2,500 in 2021—ICEDO is seeking federal support for a larger, permanent facility that could process 500 reindeer annually, or more.

“It’s a really great place to be working,” says Elanik, who is one of six full time workers at the plant. “We help our communities, help our people, and the facility is the first in the region that takes our animals that we harvest and provides them to our people.”

Scott Kasook. The plant employs six full time workers. © Elizabeth Kolb, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

The Inuvialuit Country Food Plant is a success story, and a prime example of Inuit self‐determination. But to make it all happen, first there had to be a bunch of meetings.

“We did community engagements to get feedback from our communities that we represent and see what they were looking for. We had to get buy in,” says Wade.

The next step was to run a four‐week training course for plant workers, with participants from each community. And, pass food safety health inspections by the Government of the Northwest Territories, as well as meet environmental regulations for to the distribution of country food.

Pandemic funding allowed the plant to get going. With core operations established, Wade says ICEDO wants to expand to more retailing of its products, so the plant can be self‐sustaining. Under current legislation, most country food can’t be retailed unless it’s commercially harvested. “We compensate the harvester for their time and efforts, not for the animal,” says Wade, and at least 80 per cent of all food that goes through the plant is given away for free.

Scott Kasook and Thomas Thrasher distributing food to Inuvialuit, like this fish to Sandy Stewart. © Elizabeth Kolb, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

Eventually the organization will be able to retail Inuvialuit reindeer. Until then, the plant is continuing its primary mission to address food insecurity and grow a regional food economy in the ISR.

“This also creates an economy for women who go out and pick berries, and for little kids out ice fishing with their families. They’re able to sell their excess harvest back to this plant,” says Wade. “It’s for everybody from your child to the middle‐aged family man, to your 80‐year‐old grandmother who’s sitting out on the tundra picking berries. Everybody can participate.”