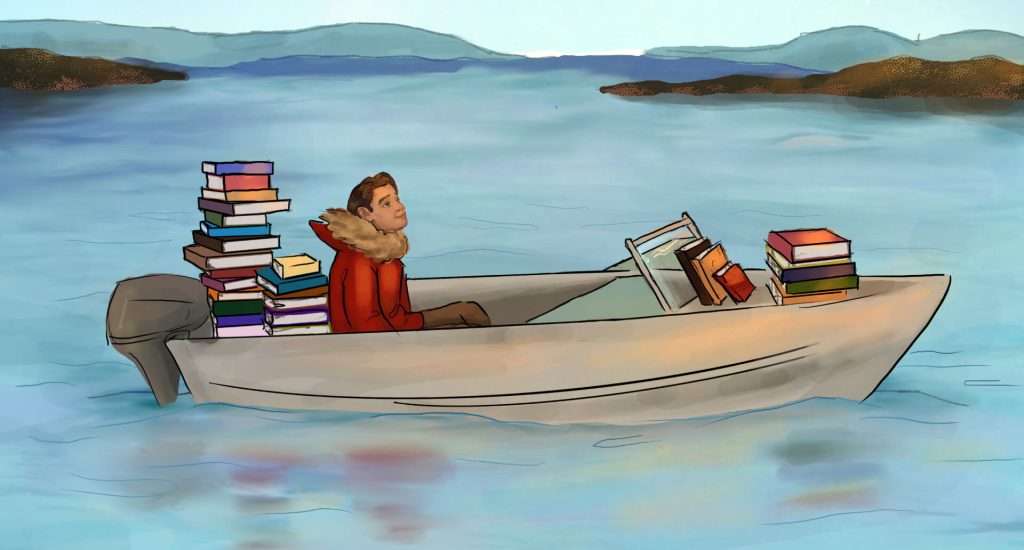

BEFORE HE DIED IN 2010, Naalak Nappaaluk loved being on a boat at sea, hunting beluga. The Kangiqsujuaq elder always brought a gun, but he preferred using his unaaq (harpoon), especially for bearded seal, says his daughter, Qiallak Nappaaluk.

BEFORE HE DIED IN 2010, Naalak Nappaaluk loved being on a boat at sea, hunting beluga. The Kangiqsujuaq elder always brought a gun, but he preferred using his unaaq (harpoon), especially for bearded seal, says his daughter, Qiallak Nappaaluk.

HUNTING HAS ALWAYS been foundational to Inuit values, perspectives, and ways of life. Hunting, and the knowledge, skills, values, language, and expertise related to hunting, are not taught in our school systems.

HERMAN AND CAROL OYAGAK first met at Kivgiq; an Iñupiat drum dancing celebration hosted in Utqiaġvik on Alaska’s North Slope.

YOU ARE SIX years old, and you’re greeted by a stranger who says they’re your therapist.

“Welcome to the playroom, you can do just about anything in here, and if there is anything you can’t do, I will let you know,” says the stranger.

MY FATHER CAUGHT his first fish and his first caribou here. It’s also where I got my first black bear and where I grew up hunting birds and other animals. This place is called Tasiraq, a lake close to my home village of Kangiqsujuaq.

IN THE VAST expanse of Nunavut, where the land stretches out like an endless white canvas and the sky meets the horizon in a seamless blend of blue and white, the tradition of qimussiq, or dog sledding, runs deep in the veins of Inuit.

THERE ARE TWO NEW INUTTITUT INSTRUCTORS running online courses through the Nunatsiavut Government Department of Language, Culture and Tourism—and they’re brother and sister. Nicholas and Vanessa Flowers of Hopedale instruct across computer screens, using colour‐coded slides Their students, myself included, are primarily adult second‐language learners who either attended or whose relatives attended residential boarding schools, and subsequently lost their language. From Nunatsiavut, the the Flowers siblings are focusing their course on Inuttitut. So far I’ve taken two online Inuttitut courses run by them.

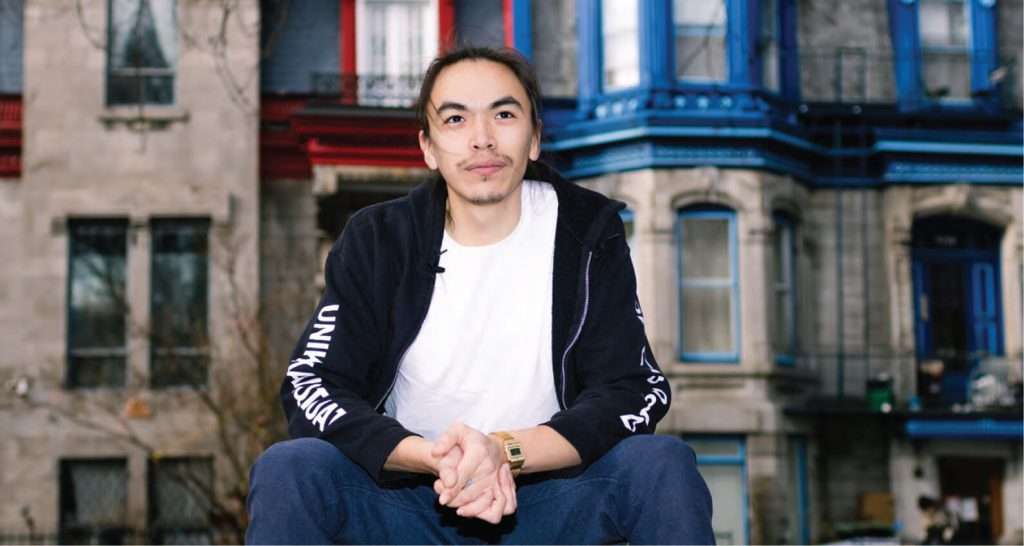

SAALI KUATA IS A MONTREAL-BASED multidisciplinary artist who works in circus, photography, and soapstone carving. He also takes roles on creative projects that teach Montrealers about Inuit history through art. Saali’s introduction to circus took place 10 years ago. After graduating high school in Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, he went off to study psychology and theatre in Montreal and found his way to becoming a full‐time artist who works closely with the Inuit community in Montreal. He lives on the island with his partner and their baby son.

POETRY HAS BEEN A LONG JOURNEY FOR ME. I started writing poetry when I realized I did not have to wait for the poetry unit each year in class. I first started writing my new book Elements in 2015 as a way to let my emotions have their say and be able to better understand them. To have your thoughts and emotions acknowledged without judgment is a peaceful feeling. You are okay, flaws and all.

I REMEMBER WELL the feeling the rugged land of home evoked in me at a young age. I had no tools then to convey this feeling, other than the word “cool.” In retrospect, I know that the warm greens of grass and lichen contrasted with the brilliant blues of sea ice just under the snowy top layer in a way that created a sense of forceful beauty. I’ve since fallen in love with being able to communicate those kinds of experiences, a passion that has led me to study English literature in university. I love how language, whether Inuktut, English, or any other, might capture what goes on in one’s head, when core memories are made, or remembered.

AS A DRUM DANCER LIVING IN IQALUIT, with family roots in Iglulik, I am most familiar with traditional drum practice of the Nunavut area, which usually entails a man composing his own song, and his wife and family singing while he drums. One song many Nunavummiut may be familiar with, Anirausilirlanga, is about when two specific stars become visible again, signifying the imminent return of the sun after the season of 24‐hour darkness.

WHEN NOEL COCKNEY heard the news of wildfire evacuations in the Northwest Territories last summer, he went straight to the Inuvik wildfire office to see how he could help. A volunteer firefighter of four years, Cockney was already trained in fighting wildland fires. Here he two-week deployment combatting one of many fires that devastated the western Canadian territory over the summer of 2023.